The Conversion Cycle:The Traditional Manufacturing Environment

The Traditional Manufacturing Environment

The conversion cycle consists of both physical and information activities related to manufacturing products for sale. The context-level data flow diagram (DFD) in Figure 7-1 illustrates the central role of the conversion cycle and its interactions with other business cycles. Production is triggered by customer orders from the revenue cycle and/or by sales forecasts from marketing. These inputs are used to set a production target and prepare a production plan, which drives production activities. Purchase requisitions for the raw materials needed to meet production objectives are sent to the purchases procedures (expenditure cycle), which prepares purchase orders for vendors. Labor used in production is transmitted to the payroll system (expenditure cycle) for payroll processing. Manufacturing costs associated with intermediate work-in-process and finished goods (FG) are sent to the general ledger (GL) and financial reporting system.

Depending on the type of product being manufactured, a company will employ one of the following production methods:

1. Continuous processing creates a homogeneous product through a continuous series of standard pro- cedures. Cement and petrochemicals are produced by this manufacturing method. Typically, under this approach firms attempt to maintain finished-goods inventory at levels needed to meet expected sales demand. The sales forecast in conjunction with information on current inventory levels triggers this process.

2. Make-to-order processing involves the fabrication of discrete products in accordance with customer specifications. This process is initiated by sales orders rather than depleted inventory levels.

3. Batch processing produces discrete groups (batches) of product. Each item in the batch is similar and requires the same raw materials and operations. To justify the cost of setting up and retooling for

each batch run, the number of items in the batch tends to be large. This is the most common method of production and is used to manufacture products such as automobiles, household appliances, canned goods, automotive tires, and textbooks. The discussion in this chapter is based on a batch processing environment.

BATCH PROCESSING SYSTEM

The DFD in Figure 7-2 provides a conceptual overview of the batch processing system, which consists of four basic processes: plan and control production, perform production operations, maintain inventory control, and perform cost accounting. As in previous chapters, the conceptual system discussion is intended to be technology-neutral. The tasks described in this section may be performed manually or by computer. The figure also depicts the primary information flows (documents) that integrate these activities and link them to other cycles and systems. Again, system documents are technology-neutral and may be hard copy or digital. We begin our study of batch processing with a review of the purpose and content of these documents.

Documents in the Batch Processing System

A manufacturing process such as that shown in Figure 7-2 could be triggered by either individual sales orders from the revenue cycle or by a sales forecast the marketing system provides. For discussion purposes, we will assume the latter. The sales forecast shows the expected demand for a firm’s FG for a given period. For some firms, marketing may produce a forecast of annual demand by product. For firms with seasonal swings in sales, the forecast will be for a shorter period (quarterly or monthly) that can be revised in accordance with economic conditions.

• The production schedule is the formal plan and authorization to begin production. This document describes the specific products to be made, the quantities to be produced in each batch, and the manufacturing timetable for starting and completing production. Figure 7-3 contains an example of a production schedule.

• The bill of materials (BOM), an example of which is illustrated in Figure 7-4, specifies the types and quantities of the raw material (RM) and subassemblies used in producing a single unit of finished product. The RM requirements for an entire batch are determined by multiplying the BOM by the number of items in the batch.

• A route sheet, illustrated in Figure 7-5, shows the production path that a particular batch of product follows during manufacturing. It is similar conceptually to a BOM. Whereas the BOM specifies material requirements, the route sheet specifies the sequence of operations (machining or assembly) and the standard time allocated to each task.

• The work order (or production order) draws from BOMs and route sheets to specify the materials and production (machining, assembly, and so on) for each batch. These, together with move tickets (described next), initiate the manufacturing process in the production departments. Figure 7-6 presents a work order.

• A move ticket, shown in Figure 7-7, records work done in each work center and authorizes the movement of the job or batch from one work center to the next.

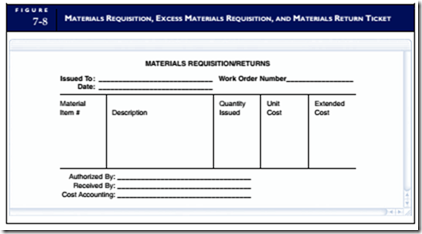

• A materials requisition authorizes the storekeeper to release materials (and subassemblies) to individuals or work centers in the production process. This document usually specifies only standard quantities. Materials needed in excess of standard amounts require separate requisitions that may be identified explicitly as excess materials requisitions. This allows for closer control over the production process by highlighting excess material usage. In some cases, less than the standard amount of material is used in production. When this happens, the work centers return the unused materials to the storeroom accompanied by a materials return ticket. Figure 7-8 presents a format that could serve all three purposes.

Batch Production Activities

The flowchart in Figure 7-9 provides a physical view of the batch processing system. The flowchart illustrates the organization functions involved, the tasks performed in each function, and the documents that

trigger or result from each task. To emphasize the physical flows in the process, documents are represented in Figure 7-9 as hard copy. Many organizations today, however, make this data transfer digitally via computerized systems that use data entry screens or capture data by scanning bar code tags. In this section, we examine three of the four conversion cycle processes depicted by the DFD in Figure 7-2. Cost accounting procedures are discussed later.

PRODUCTION PLANNING AND CONTROL. We first examine the production planning and control function. This consists of two main activities: (1) specifying materials and operations requirements and (2) production scheduling.

(if any), and the BOM. A product of this activity is the creation of purchase requisitions for additional RMs. Procedures for preparing purchase orders and acquiring inventories are the same as those described in Chapter 5. The operations requirements for the batch involve the assembly and/or manufacturing activities that will be applied to the product. This is determined by assessing route sheet specifications.

PRODUCTION SCHEDULING. The second activity of the planning and control function is production scheduling. The master schedule for a production run coordinates the production of many different batches. The schedule is influenced by time constraints, batch size, and specifications derived from BOMs and route sheets. The scheduling task also produces work orders, move tickets, and materials requisitions for each batch in the production run. A copy of each work order is sent to cost accounting to set up a new work-in-process (WIP) account for the batch. The work orders, move tickets, and materials

requisitions enter the production process and flow through the various work centers in accordance with the route sheet. To simplify the flowchart in Figure 7-9, only one work center is shown.

WORK CENTERS AND STOREKEEPING. The actual production operations begin when workers obtain raw materials from storekeeping in exchange for materials requisitions. These materials, as well as the machining and the labor required to manufacture the product, are applied in compliance with the work order. When the task is complete at a particular work center, the supervisor or other authorized person signs the move ticket, which authorizes the batch to proceed to the next work center. To evidence that a stage of production has been completed, a copy of the move ticket is sent back to production planning and control to update the open work order file. Upon receipt of the last move ticket, the open work order file is closed. The finished product along with a copy of the work order is sent to the finished goods (FG) warehouse. Also, a copy of the work order is sent to inventory control to update the FG inventory records.

Work centers also fulfill an important role in recording labor time costs. This task is handled by work center supervisors who, at the end of each workweek, send employee time cards and job tickets to the payroll and cost accounting departments, respectively.

INVENTORY CONTROL. The inventory control function consists of three main activities. First, it provides production planning and control with status reports on finished goods and raw materials inven- tory. Second, the inventory control function is continually involved in updating the raw material inventory records from materials requisitions, excess materials requisitions, and materials return tickets. Finally, upon receipt of the work order from the last work center, inventory control records the completed production by updating the finished goods inventory records.

An objective of inventory control is to minimize total inventory cost while ensuring that adequate inventories exist to meet current demand. Inventory models used to achieve this objective help answer two fundamental questions:

1. When should inventory be purchased?

2. How much inventory should be purchased?

A commonly used inventory model is the economic order quantity (EOQ) model. This model, how- ever, is based on simplifying assumptions that may not reflect the economic reality. These assumptions are:

1. Demand for the product is constant and known with certainty.

2. The lead time—the time between placing an order for inventory and its arrival—is known and constant.

3. All inventories in the order arrive at the same time.

4. The total cost per year of placing orders is a variable that decreases as the quantities ordered increase.

Ordering costs include the cost of preparing documentation, contacting vendors, processing inventory receipts, maintaining vendor accounts, and writing checks.

5. The total cost per year of holding inventories (carrying costs) is a variable that increases as the quantities ordered increase. These costs include the opportunity cost of invested funds, storage costs, property taxes, and insurance.

6. There are no quantity discounts. Therefore, the total purchase price of inventory for the year is constant.

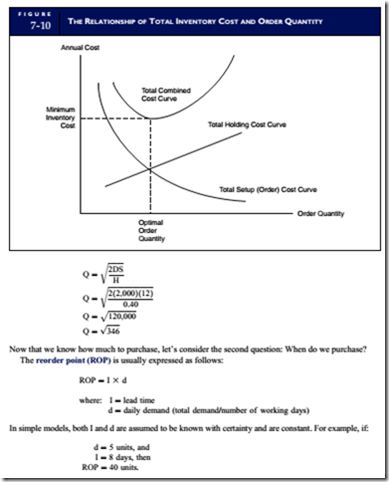

The objective of the EOQ model is to reduce total inventory costs. The significant parameters in this model are the carrying costs and the ordering costs. Figure 7-10 illustrates the relationship between these costs and order quantity. As the quantity ordered increases, the number of ordering events decreases, causing the total annual cost of ordering to decrease. As the quantity ordered increases, however, average inventory on hand increases, causing the total annual inventory carrying cost to increase. Because the total purchase price of inventory is constant (Assumption 6), we minimize total inventory costs by minimizing the total carrying cost and total ordering costs. The combined total cost curve is minimized at the intersection of the ordering-cost curve and the carrying-cost curve. This is the EOQ.

To illustrate the use of this model, consider the following example:

A company has an annual demand of 2,000 units, a per-unit order cost of $12, and a carrying cost per unit of 40 cents. Using these values, we calculate the EOQ as follows:

The assumptions of the EOQ model produce the saw-toothed inventory usage pattern illustrated in Figure 7-11. Values for Q and ROP are calculated separately for each type of inventory item. Each time inventory is reduced by sales or used in production, its new quantity on hand (QOH) is compared to its ROP. When QOH = ROP, an order is placed for the amount of Q. In our example, when inventory drops to 40 units, the firm orders 346 units.

If the parameters d and I are stable, the organization should receive the ordered inventories just as the quantity on hand reaches zero. If either or both parameters are subject to variation, however, then

additional inventories called safety stock must be added to the reorder point to avoid unanticipated stock- out events. Figure 7-12 shows an additional 10 units of safety stock to carry the firm through a lead time that could vary from 8 to 10 days. The new reorder point is 50 units. Stock-outs result in either lost sales or back-orders. A back-order is a customer order that cannot be filled because of a stock-out and will remain unfilled until the supplier receives replenishment stock.

When an organization’s inventory usage and delivery patterns depart significantly from the assumptions of the EOQ model, more sophisticated models such as the back-order quantity model and the production order quantity model may be used. However, a discussion of these models is beyond the scope of this text.

Cost Accounting Activities

Cost accounting activities of the conversion cycle record the financial effects of the physical events that are occurring in the production process. Figure 7-13 represents typical cost accounting information tasks and data flows. The cost accounting process for a given production run begins when the production planning and control department sends a copy of the original work order to the cost accounting department. This marks the beginning of the production event by causing a new record to be added to the WIP file, which is the subsidiary ledger for the WIP control account in the general ledger.

As materials and labor are added throughout the production process, documents reflecting these events flow to the cost accounting department. Inventory control sends copies of materials requisitions, excess materials requisitions, and materials returns. The various work centers send job tickets and completed move tickets. These documents, along with standards provided by the standard cost file, enable cost accounting to update the affected WIP accounts with the standard charges for direct labor, material, and manufacturing overhead (MOH). Deviations from standard usage are recorded to produce material usage, direct labor, and manufacturing overhead variances.

The receipt of the last move ticket for a particular batch signals the completion of the production process and the transfer of products from WIP to the FG inventory. At this point cost accounting closes the WIP account. Periodically, summary information regarding charges (debits) to WIP, reductions (credits) to WIP, and variances are recorded on journal vouchers and sent to the GL department for posting to the control accounts.

CONTROLS IN THE TRADITIONAL ENVIRONMENT

Recall from previous chapters the six general classes of internal control activities: transaction authorization, segregation of duties, supervision, access control, accounting records, and independent verification. Specific controls as they apply to the conversion cycle are summarized in Table 7-1 and further explained in the following section.

Transaction Authorization

The following describes the transaction authorization procedure in the conversion cycle.

1. In the traditional manufacturing environment, production planning and control authorize the production activity via a formal work order. This document reflects production requirements, which are the difference between the expected demand for products (based on the sales forecast) and the FG inventory on hand.

2. Move tickets signed by the supervisor in each work center authorize activities for each batch and for the movement of products through the various work centers.

3. Materials requisitions and excess materials requisitions authorize the storekeeper to release materials to the work centers.

Segregation of Duties

One objective of this control procedure is to separate the tasks of transaction authorization and transaction processing. As a result, the production planning and control department is organizationally segregated from the work centers.

Another control objective is to segregate record keeping from asset custody. The following separations apply:

1. Inventory control maintains accounting records for RM and FG inventories. This activity is kept separate from the materials storeroom and from the FG warehouse functions, which have custody of these assets.

2. Similarly, the cost accounting function accounts for WIP and should be separate from the work cen- ters in the production process.

Finally, to maintain the independence of the GL function as a verification step, the GL department must be separate from departments keeping subsidiary accounts. Therefore, the GL department is organizationally segregated from inventory control and cost accounting.

Supervision

The following supervision procedures apply to the conversion cycle:

1. The supervisors in the work centers oversee the usage of RM in the production process. This helps to ensure that all materials released from stores are used in production and that waste is minimized. Employee time cards and job tickets must also be checked for accuracy.

2. Supervisors also observe and review timekeeping activities. This promotes accurate employee time cards and job tickets.

Access Control

The conversion cycle allows both direct and indirect access to assets.

DIRECT ACCESS TO ASSETS. The nature of the physical product and the production process influences the type of access controls needed.

1. Firms often limit access to sensitive areas, such as storerooms, production work centers, and FG warehouses. Control methods used include identification badges, security guards, observation devices, and various electronic sensors and alarms.

2. The use of standard costs provides a type of access control. By specifying the quantities of material and labor authorized for each product, the firm limits unauthorized access to those resources. To obtain excess quantities requires special authorization and formal documentation.

INDIRECT ACCESS TO ASSETS. Assets, such as cash and inventories, can be manipulated through access to the source documents that control them. In the conversion cycle, critical documents include materials requisitions, excess materials requisitions, and employee time cards. A method of control that also supports an audit trail is the use of prenumbered documents.

Accounting Records

As we have seen in preceding chapters, the objective of this control technique is to establish an audit trail for each transaction. In the conversion cycle this is accomplished through the use of work orders, cost sheets, move tickets, job tickets, materials requisitions, the WIP file, and the FG inventory file. By pre- numbering source documents and referencing these in the WIP records, a company can trace every item of FG inventory back through the production process to its source. This is essential in detecting errors in production and record keeping, locating batches lost in production, and performing periodic audits.

Independent Verification

Verification steps in the conversion cycle are performed as follows:

1. Cost accounting reconciles the materials and labor usage taken from materials requisitions and job tickets with the prescribed standards. Cost accounting personnel may then identify departures from prescribed standards, which are formally reported as variances. In the traditional manufacturing envi- ronment, calculated variances are an important source of data for the management reporting system.

2. The GL department also fulfills an important verification function by checking the total movement of products from WIP to FG. This is done by reconciling journal vouchers from cost accounting and summaries of the inventory subsidiary ledger from inventory control.

3. Finally, internal and external auditors periodically verify the RM and FG inventories on hand through a physical count. They compare actual quantities against the inventory records and make adjustments to the records when necessary.

Comments

Post a Comment