Financial Reporting and Management Reporting Systems:The Management Reporting System.

The Management Reporting System

Management reporting is often called discretionary reporting because it is not mandated, as is financial reporting. One could take issue with the term discretionary, however, and argue that an effective management reporting system (MRS) is mandated by SOX legislation, which requires that all public companies monitor and report on the effectiveness of internal controls over financial reporting. Indeed, management reporting has long been recognized as a critical element of an organization’s internal control structure. An MRS that directs management’s attention to problems on a timely basis promotes effective management and thus supports the organization’s business objectives.

Factors That Influence the MRS

Designing an effective MRS requires an understanding of the information that managers need to deal with the problems they face. This section examines several topics that provide insight into factors that influnce management information needs. These are management principles; management function, level, and decision type; problem structure; types of management reports; responsibility accounting; and behavioral considerations.

MANAGEMENT PRINCIPLES

Management principles provide insight into management information needs. The principles that most directly influence the MRS are formalization of tasks, responsibility and authority, span of control, and management by exception.

Formalization of Tasks

The formalization of tasks principle suggests that management should structure the firm around the tasks it performs rather than around individuals with unique skills. Under this principle, organizational areas are subdivided into tasks that represent full-time job positions. Each position must have clearly defined limits of responsibility.

The purpose of formalization of tasks is to avoid an organizational structure in which the organization’s performance, stability, and continued existence depend on specific individuals. The organizational chart in Figure 8-14 shows some typical job positions in a manufacturing firm.

Although a firm’s most valuable resource is its employees, it does not own the resource. Sooner or later, key individuals leave and take their skills with them. By formalizing tasks, the firm can more easily recruit individuals to fill standard positions left open by those who leave. In addition, the formalization of tasks promotes internal control. With employee responsibilities formalized and clearly specified, management can construct an organization that avoids assigning incompatible tasks to an individual.

IMPLICATIONS FOR THE MRS. Formalizing the tasks of the firm allows formal specification of the information needed to support the tasks. Thus, when a personnel change occurs, the information the new employee will need is essentially the same as for his or her predecessor. The information system must focus on the task, not the individual performing the task. Otherwise, information requirements would need to be reassessed with the appointment of each new individual to the position. Also, internal control is strengthened by restricting information based on need as defined by the task, rather than the whim or desire of the user.

Responsibility and Authority

The principle of responsibility refers to an individual’s obligation to achieve desired results. Responsibility is closely related to the principle of authority. If a manager delegates responsibility to a subordinate,

he or she must also grant the subordinate the authority to make decisions within the limits of that responsibility. In a business organization, managers delegate responsibility and authority downward through the organizational hierarchy from superior to subordinates.

IMPLICATIONS FOR THE MRS. The principles of responsibility and authority define the vertical reporting channels of the firm through which information flows. The manager’s location in the reporting channel influences the scope and detail of the information reported. Managers at higher levels usually require more summarized information. Managers at lower levels receive information that is more detailed. In designing a reporting structure, the analyst must consider the manager’s position in the reporting channel.

Span of Control

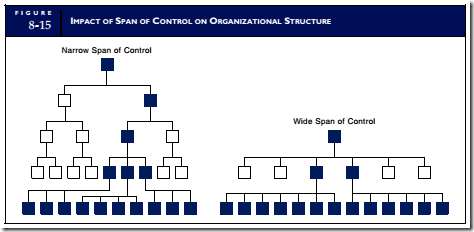

A manager’s span of control refers to the number of subordinates directly under his or her control. The size of the span has an impact on the organization’s physical structure. A firm with a narrow span of control has fewer subordinates reporting directly to managers. These firms tend to have tall, narrow structures with several layers of management. Firms with broad spans of control (more subordinates reporting to each manager) tend to have wide structures, with fewer levels of management. Figure 8-15 illustrates the relationship between span of control and organizational structure.

Organizational behavior research suggests that wider spans of control are preferable because they allow more employee autonomy in decision making. This may translate into better employee morale and increased motivation. An important consideration in setting the span of control is the nature of the task. The more routine and structured the task, the more subordinates one manager can control. Therefore, routine tasks tend to be associated with a broad span of control. Less structured or highly technical tasks of- ten require a good deal of management participation on task-related problems. This close interaction reduces the manager’s span of control.

IMPLICATIONS FOR THE MRS. Managers with narrow spans of control are closely involved with the details of the operation and with specific decisions. Broad spans of control remove managers from these details. These managers delegate more of their decision-making authority to their subordinates. The different management approaches require different information. Managers with narrow spans of control require detailed reports. Managers with broad control responsibilities operate most effectively with summarized information.

Management by Exception

The principle of management by exception suggests that managers should limit their attention to potential problem areas (that is, exceptions) rather than being involved with every activity or decision. Managers thus maintain control without being overwhelmed by the details.

IMPLICATIONS FOR THE MRS. Managers need information that identifies operations or resources at risk of going out of control. Reports should support management by exception by focusing on changes in key factors that are symptomatic of potential problems. Unnecessary details that may draw attention

away from important facts should be excluded from reports. For example, an inventory exception report may be used to identify items of inventory that turn over more slowly or go out of stock more frequently than normal. Management attention must be focused on these exceptions. The majority of inventory items that fluctuate within normal levels should not be included in the report.

MANAGEMENT FUNCTION, LEVEL, AND DECISION TYPE

The management functions of planning and control have a profound effect on the MRS. The planning function is concerned with making decisions about the future activities of the organization. Planning can be long range or short range. Long-range planning usually encompasses a period of between 1 and 5 years, but this varies among industries. For example, a public utility may plan 15 years ahead in the construction of a new power plant, while a computer manufacturer deals in a time frame of only 1 or 2 years in the planning of new products. Long-range planning involves a variety of tasks, including setting the goals and objectives of the firm, planning the growth and optimum size of the firm, and deciding on the degree of diversification among the firm’s products.

Short-term planning involves the implementation of specific plans that are needed to achieve the objectives of the long-range plan. Examples include planning the marketing and promotion for a new product, preparing a production schedule for the month, and providing department heads with budgetary goals for the next 3 months.

The control function ensures that the activities of the firm conform to the plan. This entails evaluating the operational process (or individual) against a predetermined standard and, when necessary, taking corrective action. Effective control takes place in the present time frame and is triggered by feedback information that advises the manager about the status of the operation being controlled.

Planning and control decisions are frequently classified into four categories: strategic planning, tactical planning, managerial control, and operational control. Figure 8-16 relates these decisions to managerial levels.

Strategic Planning Decisions

Figure 8-16 shows that top-level managers make strategic planning decisions, including:

• Setting the goals and objectives of the firm.

• Determining the scope of business activities, such as desired market share, markets the firm wishes to enter or abandon, the addition of new product lines and the termination of old ones, and merger and acquisition decisions.

• Determining or modifying the organization’s structure.

• Setting the management philosophy.

Strategic planning decisions have the following characteristics:

• They have long-term time frames. Because they deal with the future, managers making strategic decisions require information that supports forecasting.

• They require highly summarized information. Strategic decisions focus on general trends rather than detail-specific activities.

• They tend to be nonrecurring. Strategic decisions are usually one-time events. As a result, there is little historical information available to support the specific decision.

• Strategic decisions are associated with a high degree of uncertainty. The decision maker must rely on insight and intuition. Judgment is often central to the success of the decision.

• They are broad in scope and have a profound impact on the firm. Once made, strategic decisions permanently affect the organization at all levels.

• Strategic decisions require external as well as internal sources of information.

Tactical Planning Decisions

Tactical planning decisions are subordinate to strategic decisions and are made by middle management (see Figure 8-16). These decisions are shorter term, more specific, recurring, have more certain outcomes, and have a lesser impact on the firm than strategic decisions. For example, assume that the president of a manufacturing firm makes the strategic decision to increase sales and production by 100,000 units over the prior year’s level. One tactical decision that must result from this is setting the monthly production schedule to accomplish the strategic goal.

Management Control Decisions

Management control involves motivating managers in all functional areas to use resources, including materials, personnel, and financial assets, as productively as possible. The supervising manager compares the performance of his or her subordinate manager to pre-established standards. If the subordinate does not meet the standard, the supervisor takes corrective action. When the subordinate meets or exceeds expectations, he or she may be rewarded.

Uncertainty surrounds management control decisions because it is difficult to separate the manager’s performance from that of his or her operational unit. We often lack both the criteria for specifying management control standards and the objective techniques for measuring performance. For example, assume that a firm’s top management places its most effective and competent middle manager in charge of a business segment that is performing poorly. The manager’s task is to revitalize the operations of the unit, and doing so requires a massive infusion of resources. The segment will operate in the red for some time until it establishes a foothold in the market. Measuring the performance of this manager in the short term may be difficult. Traditional measures of profit, such as return on investment (which measures the performance of the operational unit itself), would not really reflect the manager’s performance. We shall examine this topic in more depth later in the chapter.

Operational Control Decisions

Operational control ensures that the firm operates in accordance with pre-established criteria. Figure 8-16 shows that operations managers exercise operational control. Operational control decisions are narrower and more focused than tactical decisions because they are concerned with the routine tasks of operations. Operational control decisions are more structured than management control decisions, more dependent on details than planning decisions, and have a shorter time frame than tactical or strategic decisions. These decisions are associated with a fairly high degree of certainty. In other words, identified symptoms tend to be good indicators of the root problem, and corrective actions tend to be obvious. This degree of certainty makes it easier to establish meaningful criteria for measuring performance. Operational control decisions have three basic elements: setting standards, evaluating performance, and taking corrective action.

STANDARDS. Standards are pre-established levels of performance that managers believe are attainable. Standards apply to all aspects of operations, such as sales volume, quality control over production, costs for inventory items, material usage in the production of products, and labor costs in production. Once established, these standards become the basis for evaluating performance.

PERFORMANCE EVALUATION. The decision maker compares the performance of the operation in question against the standard. The difference between the two is the variance. For example, a price variance for an item of inventory is the difference between the expected price—the standard—and the price actually paid. If the actual price is greater than the standard, the variance is said to be unfavorable. If the actual price is less than the standard, the variance is favorable.

TAKING CORRECTIVE ACTION. After comparing the performance to the standard, the manager takes action to remedy any out-of-control condition. Recall from Chapter 3, however, that we must apply extreme caution when taking corrective action. An inappropriate response to performance measures may have undesirable results. For example, to achieve a favorable price variance, the purchasing agent may pursue the low-price vendors of raw materials and sacrifice quality. If the lower-quality raw materials result in excessive quantities being used in production because of higher-than-normal waste, the firm will experience an unfavorable material usage variance. The unfavorable usage variance may completely off- set the favorable price variance to create an unfavorable total variance.

Table 8-1 classifies strategic planning, tactical planning, management control, and operational control decisions in terms of time frame, scope, level of details, recurrence, and certainty.

PROBLEM STRUCTURE

The structure of a problem reflects how well the decision maker understands the problem. Structure has three elements.7

1. Data—the values used to represent factors that are relevant to the problem.

2. Procedures—the sequence of steps or decision rules used in solving the problem.

3. Objectives—the results the decision maker desires to attain by solving the problem.

When all three elements are known with certainty, the problem is structured. Payroll calculation is an example of a structured problem:

1. We can identify the data for this calculation with certainty (hours worked, hourly rate, withholdings, tax rate, and so on).

2. Payroll procedures are known with certainty:

3. The objective of payroll is to discharge the firm’s financial obligation to its employees.

Structured problems do not present unique situations to the decision maker and, because their information requirements can be anticipated, they are well suited for traditional data processing techniques. In effect, the designer who specifies the procedures and codes the programs solves the problem.

Unstructured Problems

Problems are unstructured when any of the three characteristics identified previously are not known with certainty. In other words, an unstructured problem is one for which we have no precise solution techniques. Either the data requirements are uncertain, the procedures are not specified, or the solution objectives have not been fully developed. Such a problem is normally complex and engages the decision maker in a unique situation. In these situations, the systems analyst cannot fully anticipate user information needs, rendering traditional data processing techniques ineffective.

Figure 8-17 illustrates the relationship between problem structure and organizational level. We see from the figure that lower levels of management deal more with fully structured problems, whereas upper management deals with unstructured problems. Middle-level managers tend to work with partially structured problems. Keep in mind that these structural classifications are generalizations. Top managers also deal with some highly structured problems, and lower-level managers sometimes face problems that lack structure.

Figure 8-17 also shows the use of information systems by different levels of management. The traditional information system deals most effectively with fully structured problems. Therefore, operations management and tactical management receive the greatest benefit from these systems. Because management control and strategic planning decisions lack structure, the managers who make these decisions of- ten do not receive adequate support from traditional systems alone.

Reports are the formal vehicles for conveying information to managers. The term report tends to imply a written message presented on sheets of paper. In fact, a management report may be a paper document or a digital image displayed on a computer terminal. The report may express information in verbal, numeric, or graphic form, or any combination of these.

Report Objectives

Chapter 1 made the distinction between information and data. Recall that information leads the user to an action. Therefore, to be useful, reports must have information content. Their value is the effect they have on users. This is expressed in two general reporting objectives: (1) to reduce the level of uncertainty asso- ciated with a problem facing the decision maker, and (2) to influence the decision maker’s behavior in a positive way. Reports that fail to accomplish these objectives lack information content and have no value. In fact, reliance on such reports may lead to dysfunctional behavior (discussed later). Management reports fall into two broad classes: programmed reports and ad hoc reports.

Programmed Reporting

Programmed reports provide information to solve problems that users have anticipated. There are two subclasses of programmed reports: scheduled reports and on-demand reports. The MRS produces scheduled reports according to an established time frame. This could be daily, weekly, quarterly, and so on. Examples of such reports are a daily listing of sales, a weekly payroll action report, and annual financial statements. On-demand reports are triggered by events, not by the passage of time. For example, when inventories fall to their pre-established reorder points, the system sends an inventory reorder report to the purchasing agent. Another example is an accounts receivable manager responding to a customer problem over the telephone. The manager can, on demand, display the customer’s account history on the computer screen. Note that this query capability is the product of an anticipated need. This is quite different from the ad hoc reports that we discuss later. Table 8-2 lists examples of typical programmed reports and identifies them as scheduled or on-demand.

Report Attributes

To be effective, a report must possess the following attributes: relevance, summarization, exception orientation, accuracy, completeness, timeliness, and conciseness. Each of these report attributes is discussed in the following section.

RELEVANCE. Each element of information in a report must support the manager’s decision. Irrelevancies waste resources and may even be dysfunctional by distracting a manager’s attention from the information content of the report.

SUMMARIZATION. Reports should be summarized according to the level of the manager within the organizational hierarchy. In general, the degree of summarization becomes greater as information flows from lower management upward to top management.

EXCEPTION ORIENTATION. Control reports should identify activities that are at risk of going out of control and should ignore activities that are under control. For example, consider a purchasing agent with ordering responsibility for an inventory of 10,000 different items. If the agent received a daily report containing the actual balances of every item, he or she would search through 10,000 items to identify a few that need reordering. An exception-oriented report would identify only those inventory items that have fallen to their reorder levels. From this report, the agent could easily prepare purchase orders.

ACCURACY. Information in reports must be free of material errors. A material error will cause the user to make the wrong decision (or fail to make a required decision). We often sacrifice accuracy for timely information. In situations that require quick responses, the manager must factor this trade-off into the decision-making process.

COMPLETENESS. Information must be as complete as possible. Ideally, no piece of information that is essential to the decision should be missing from the report. Like the attribute of accuracy, we some- times must sacrifice completeness in favor of timely information.

TIMELINESS. If managers always had time on their side, they may never make bad decisions. How- ever, managers cannot always wait until they have all the facts before they act. Timely information that is sufficiently complete and accurate is more valuable than perfect information that comes too late to use. Therefore, the MRS must provide managers with timely information. Usually, information can be no older than the period to which it pertains. For example, if each week a manager decides on inventory acquisitions based on a weekly inventory status report, the information in the report should be no more than a week old.

CONCISENESS. Information in the report should be presented as concisely as possible. Reports should use coding schemes to represent complex data classifications and provide all the necessary calculations (such as extensions and variances) for the user. In addition, information should be clearly presented with titles for all values.

Ad Hoc Reporting

Managers cannot always anticipate their information needs. This is particularly true for top and middle management. In the dynamic business world, problems arise that require new information on short notice, and there may be insufficient time to write traditional computer programs to produce the required information. In the past, these needs often went unsatisfied. Now database technology provides direct inquiry and report generation capabilities. Managers with limited computer background can quickly produce ad hoc reports from a terminal or PC, without the assistance of data processing professionals.

Increases in computing power, point-of-transaction scanners, and continuous reductions in data storage costs have enabled organizations to accumulate massive quantities of raw data. This data resource is now being tapped to support ad hoc reporting needs through a concept known as data mining.

Data mining is the process of selecting, exploring, and modeling large amounts of data to uncover relationships and global patterns that exist in large databases but are hidden among the vast amount of facts. This involves sophisticated techniques such as database queries and artificial intelligence that model real-world phenomena from data collected from a variety of sources, including transaction processing systems, customer history databases, and demographics data from external sources such as credit bureaus. Managers employ two general approaches to data mining: verification and discovery.

The verification model uses a drill-down technique to either verify or reject a user’s hypothesis. For example, assume a marketing manager needs to identify the best target market, as a subset of the organization’s entire customer base, for an ad campaign for a new product. The data mining software will exam- ine the firm’s historical data about customer sales and demographic information to reveal comparable sales and the demographic characteristics shared by those purchasers. This subset of the customer base can then be used to focus the promotion campaign.

The discovery model uses data mining to discover previously unknown but important information that is hidden within the data. This model employs inductive learning to infer information from detailed data by searching for recurring patterns, trends, and generalizations. This approach is fundamentally different from the verification model in that the data are searched with no specific hypothesis driving the process. For example, a company may apply discovery techniques to identify customer buying patterns and gain a better understanding of customer motivations and behavior.

A central feature of a successful data mining initiative is a data warehouse of archived operational data. A data warehouse is a relational database management system that has been designed specifically to meet the needs of data mining. The warehouse is a central location that contains operational data about current events (within the past 24 hours) as well as events that have transpired over many years. Data are coded and stored in the warehouse in detail and at various degrees of aggregation to facilitate identification of recurring patterns and trends.

Management decision making can be greatly enhanced through data mining, but only if the appropriate data have been identified, collected, and stored in the data warehouse. Because many of the important issues related to data mining and warehousing require an understanding of relational database technology, these topics are examined further in Chapters 9 and 11.

RESPONSIBILITY ACCOUNTING

A large part of management reporting involves responsibility accounting. This concept implies that every economic event that affects the organization is the responsibility of and can be traced to an individual manager. The responsibility accounting system personalizes performance by saying to the manager, ‘‘This is your original budget, and this is how your performance for the period compares to your budget.’’ Most organizations structure their responsibility reporting system around areas of responsibility in the firm. A fundamental principle of this concept is that responsibility area managers are accountable only for items (costs, revenues, and investments) that they control.

The flow of information in responsibility systems is both downward and upward through the information channels. Figure 8-18 illustrates this pattern. These top-down and bottom-up information flows rep- resent the two phases of responsibility accounting: (1) creating a set of financial performance goals (budgets) pertinent to the manager’s responsibilities, and (2) reporting and measuring actual performance as compared to these goals.

Setting Financial Goals: The Budget Process

The budget process helps management achieve its financial objectives by establishing measurable goals for each organizational segment. This mechanism conveys to the segment managers the standards that senior managers will use for measuring their performance. Budget information flows downward and becomes increasingly detailed as it moves to lower levels of management. Figure 8-19 shows the distribution of budget information through three levels of management.

Measuring and Reporting Performance

Performance measurement and reporting take place at each operational segment in the firm. This information flows upward as responsibility reports to senior levels of management. Figure 8-20 shows the relationship between levels of responsibility reports. Notice how the information in the reports becomes increasingly summarized at each higher level of management.

Responsibility Centers

To achieve accountability, business entities frequently organize their operations into units called responsibility centers. The most common forms of responsibility centers are cost centers, profit centers, and investment centers.

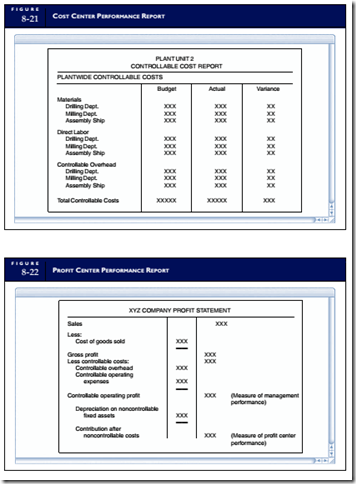

COST CENTERS. A cost center is an organizational unit with responsibility for cost management within budgetary limits. For example, a production department may be responsible for meeting its production obligation while keeping production costs (labor, materials, and overhead) within the budgeted amount. The performance report for the cost center manager reflects its controllable cost behavior by focusing on budgeted costs, actual costs, and variances from budget. Figure 8-21 shows an example of a cost center performance report. Performance measurements should not consider costs that are outside the manager’s control, such as investments in plant equipment or depreciation on the building.

PROFIT CENTERS. A profit center manager has responsibility for both cost control and revenue generation. For example, the local manager of a national department store chain may be responsible for decisions about:

• Which items of merchandise to stock in the store.

• What prices to charge.

• The kind of promotional activities for products.

• The level of advertising.

• The size of the staff and the hiring of employees.

• Building maintenance and limited capital improvements.

The performance report for the profit center manager is different from that of the cost center. Nevertheless, the reporting emphasis for both should be on controllable items. Figure 8-22 is an example of a profit center report. Whereas only controllable items are used to assess the manager’s performance, the profit center itself is assessed by its contribution after noncontrollable costs.

INVESTMENT CENTERS. The manager of an investment center has the general authority to make decisions that profoundly affect the organization. Assume that a division of a corporation is an investment center with the objective of maximizing the return on its investment assets. The division manager’s range of responsibilities includes cost management, product development, marketing, distribution, and capital disposition through investments of funds in projects and ventures that earn a desired rate of return. Figure 8-23 illustrates the performance report for an investment center.

BEHAVIORAL CONSIDERATIONS

Goal Congruence

Earlier in this chapter, we touched on the management principles of authority, responsibility, and the formalization of tasks. When properly applied within an organization, these principles promote goal congruence. Lower-level managers pursuing their own objectives contribute in a positive way to the objectives of their superiors. For example, by controlling costs, a production supervisor contributes to the division manager’s goal of profitability. Thus, as individual managers serve their own best interests they also serve the best interests of the organization.

A carefully structured MRS plays an important role in promoting and preserving goal congruence. On the other hand, a badly designed MRS can cause dysfunctional actions that are in opposition to the orga- nization’s objectives. Two pitfalls that cause managers to act dysfunctionally are information overload and inappropriate performance measures.

Information Overload

Information overload occurs when a manager receives more information than he or she can assimilate. This happens when designers of the reporting system do not properly consider the manager’s organizational level and span of control. For example, consider the information volume that would flow to the president if the reports were not properly summarized (refer to Figure 8-18). The details required by lower-level managers would quickly overload the president’s decision-making process. Although the report may have many of the information attributes discussed earlier (complete, accurate, timely, and con- cise), it may be useless if not properly summarized.

Information overload causes managers to disregard their formal information and rely on informal cues to help them make decisions. Thus, the formal information system is replaced by heuristics (rules of thumb), tips, hunches, and guesses. The resulting decisions run a high risk of being suboptimal and dysfunctional.

Inappropriate Performance Measures

Recall that one purpose of a report is to stimulate behavior consistent with the objectives of the firm. When inappropriate performance measures are used, however, the report can have the opposite effect. Let’s see how this can happen using a common performance measure—return on investment (ROI).

Assume that the corporate management of an organization evaluates division management performance solely on the basis of ROI. Each manager’s objective is to maximize ROI. Naturally, the organization wants this to happen through prudent cost management and increased profit margins. However, when ROI is used as the single criterion for measuring performance, the criterion itself becomes the focus of attention and object of manipulation. We illustrate this point with the multi- period investment center report in Figure 8-24. Notice how actual ROI went up in 2008 and exceeded the budgeted ROI in 2009. On the surface, this looks like favorable performance. How- ever, a closer analysis of the cost and revenue figures gives a different picture. Actual sales were below budgeted sales for 2009, but the shortfall in revenue was offset by reductions in discretionary operating expenditures (employee training and plant maintenance). The ROI figure is further improved by reducing investments in inventory and plant equipment (fixed assets) to lower the asset base.

The manager took actions that increased ROI but were dysfunctional to the organization. Usually, such tactics can succeed in the short run only. As the plant equipment starts to wear out, customer dissatisfaction increases (because of stock-outs), and employee dissent becomes epidemic. The ROI figure will then begin to reflect the economic reality. By that time, however, the manager may have been promoted based on the perception of good performance, and his or her successor will inherit the problems left behind.

The use of any single-criterion performance measure can impose personal goals on managers that conflict with organizational goals and result in dysfunctional behavior.

Consider the following examples:

1. The use of price variance to evaluate a purchasing agent can affect the quality of the items purchased.

2. The use of quotas (such as units produced) to evaluate a supervisor can affect quality control, material usage efficiency, labor relations, and plant maintenance.

3. The use of profit measures such as ROI, net income, and contribution margin can affect plant investment, employee training, inventory reserve levels, customer satisfaction, and labor relations.

Performance measures should consider all relevant aspects of a manager’s responsibility. In addition to measures of general performance (such as ROI), management should measure trends in key variables such as sales, cost of goods sold, operating expenses, and asset levels. Nonfinancial measures such as product leadership, personnel development, employee attitudes, and public responsibility may also be relevant in assessing management performance.

Comments

Post a Comment