Construct, Deliver and Maintain Systems Project:Choosing a Package

Choosing a Package

Having made the decision to purchase commercial software, the systems development team is now faced with the task of choosing the package that best satisfies the organization’s needs. On the surface, there may appear to be no clear-cut best choice from the many options available. The following four-step procedure can help structure this decision-making process by establishing decision criteria and identifying key differences between options.

Step 1: Needs Analysis

As with in-house development, the commercial option begins with an analysis of user needs. These are formally presented in a statement of systems requirements that provides a basis for choosing between competing alternatives. For example, the stated requirement of the new system may be to:

1. Support the accounting and reporting requirements of federal, state, and local agencies.

2. Provide access to information in a timely and efficient manner.

3. Simultaneously support both accrual accounting and fund accounting systems.

4. Increase transaction processing capacity.

5. Reduce the cost of current operations.

6. Improve user productivity.

7. Reduce processing errors.

8. Support batch and real-time processing.

9. Provide automatic general ledger reconciliations.

10. Be expandable and flexible to accommodate growth and changes in future needs.

The systems requirements should be as detailed as the user’s technical background permits. Detailed specifications enable users to narrow the search to only those packages most likely to satisfy their needs. Although computer literacy is a distinct advantage in this step, the technically inexperienced user can still compile a meaningful list of desirable features that the system should possess. For example, the user should address such items of importance as compliance with accounting conventions, special control and transaction volume requirements, and so on.

Step 2: Send Out the Request for Proposals

Systems requirements are summarized in a document called a request for proposal (RFP) that is sent to each prospective vendor. A letter of transmittal accompanies the RFP to explain to the vendor the nature of the problem, the objectives of the system, and the deadline for proposal submission.

The RFP provides a format for vendor responses and thus a comparative basis for initial screening. Some vendors will choose not to respond to the RFP, while others will propose packages that clearly do not meet the stated requirements. The reviewer should attempt to select from these responses those proposals that are feasible alternatives.

Step 3: Gather Facts

In this next step in the selection process, the objective is to identify and capture relevant facts about each vendor’s system. The following describes techniques for fact gathering.

VENDOR PRESENTATIONS. At some point during the review, vendors should be invited to make formal presentations of their systems at the user’s premises. This provides the principal decision makers and users with an opportunity to observe the product firsthand.

Technical demonstrations are usually given at these presentations using modified versions of the pack- ages that run on microcomputers. This provides an opportunity to obtain answers to detailed questions. Sufficient time should therefore be allotted for an in-depth demonstration followed by a question-and- answer period. If vendor representatives are unable or unwilling to demonstrate the full range of system capabilities or to deal with specific questions from the audience, this may indicate a functional deficiency of the system.

Failure to gain satisfactory responses from vendor representatives may also be a sign of their technical incompetence. The representatives either do not understand the user’s problem or their own system and how it relates to the user’s situation. In either case, the user has cause to question the vendor’s ability to deliver a quality product and to provide adequate support.

BENCHMARK PROBLEMS. One often-used technique for measuring the relative performance of competing systems is to establish a benchmark problem for them to solve. The benchmark problem could consist of important transactions or tasks that key components of the system perform. In the benchmark example illustrated in Figure 14-22, both systems are given the same data and processing task. The results of processing are compared on criteria such as speed, accuracy, and efficiency in performing the task.

VENDOR SUPPORT. For some organizations, vendor support is an important criterion in systems selection. The desired level of support should be carefully considered. Organizations with competent in- house systems professionals may need less vendor support than firms without such internal resources. Support can vary greatly from vendor to vendor. Some vendors provide full-service support, including:

• Client training

• User and technical documentation

• Warranties

• Maintenance programs to implement system enhancements

• Toll-free help numbers

• Annual seminars to obtain input from users and apprise them of the latest developments

At the other extreme, some vendors provide virtually no support. The buyer should be wary of a promise of support that seems too good to be true, because it probably is. The level of support the vendor pro- vides can account for a large portion of its product’s price. To avoid dump-and-run vendors, the buyer must be prepared to pay for support.

CONTACT USER GROUPS. A vendor’s current user list is an important source of information. The prospective user, not the vendor, should select a representative sample of users with the latest version of the package and with similar computer configurations. A standard set of questions directed to these users will provide information for comparing packages. The following list is an example of the type of questions to ask:

• When did you purchase the package?

• Which other vendors did you review?

• Why did you select this package?

• Are you satisfied with the package?

• Are you satisfied with the vendor support?

• Does the system perform as advertised?

• Were modifications required?

• What type of training did the vendor provide?

• What is the quality of the documentation?

• Have any major problems been encountered?

• Do you subscribe to the vendor’s maintenance program?

• If so, do you receive enhancements?

To reiterate an important point, the prospective user, not the vendor, should select the user references. This provides for a more objective appraisal and reduces the possibility of receiving biased information from showcase installations.

Step 4: Analyze the Findings and Make a Final Selection

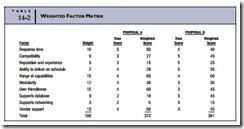

The final step in the selection process is to analyze the facts and choose the best package. The principal problem is dealing with the many qualitative aspects of this decision. A popular technique for structuring and analyzing qualitative variables is the weighted factor matrix. The technique requires constructing a table similar to the one illustrated in Table 14-2. This table shows a comparison between only two proposals, those of Vendor A and Vendor B. In practice, the approach can be applied to all the vendors under consideration.

The table presents the relevant decision criteria under the heading Factor. Each decision factor is assigned a weight that implies its relative importance to the user. Two steps are critical to this analysis technique: (1) identify all relevant decision factors and (2) assign realistic weights to each factor. As these factors represent all of the relevant decision criteria, their weights should total 100 percent. These weights will likely vary among decision makers. One reviewer may consider vendor support an important factor and thus assign a high numeric value to its weight. Another decision maker may give this a low weight because support is not important in his or her firm, relative to other factors.

After assigning weights, each vendor package is evaluated according to its performance in each factor category. Based upon the facts gathered in the previous steps, each individual factor is scored on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 is poor performance and 5 is excellent. The weighted scores are computed by multiplying the raw score by the weight for each factor. Using the previous example, a weight of 15 for vendor support is multiplied by a score of 4 for Vendor A and 3 for Vendor B, yielding the weighted scores of 60 and 45, respectively.

The weighted scores are then totaled, and each vendor is assigned a composite score. This is the vendor’s overall performance index. Table 14-2 shows a score for Vendor B of 391 and 372 for Vendor A. This composite score suggests that Vendor B’s product is rated slightly higher than Vendor A’s.

This analysis must be taken a step further to include financial considerations. For example, assume Proposal A costs $150,000 and Proposal B costs $190,000. An overall performance/cost index is computed as follows.

This means that Proposal A provides 2.48 units of performance per $1,000 versus only 2.06 units per $1,000 from Proposal B. Therefore, Proposal A provides the greater value for the cost.

The option with the highest performance/cost ratio is the more economically feasible choice. Of course, this analysis rests on the user’s ability to identify all relevant decision factors and assign to them weights that reflect their relative importance to the decision. If any relevant factors are omitted or if their weights are misstated, the results of the analysis will be misleading.

Comments

Post a Comment