IT Controls Part I,Sarbanes-Oxley and IT Governance:Disaster Recovery Planning.

Disaster Recovery Planning

Some disasters cannot be prevented or evaded. Recent events include hurricanes, widespread flooding, earthquakes, and the events of September 11, 2001. The survival of a firm affected by a disaster depends on how it reacts. With careful contingency planning, the full impact of a disaster can be absorbed and the organization can still recover.

A disaster recovery plan (DRP) is a comprehensive statement of all actions to be taken before, during, and after a disaster, along with documented, tested procedures that will ensure the continuity of operations. Although the details of each plan are unique to the needs of the organization, all workable plans possess common features. The remainder of this section is devoted to a discussion of the following control issues: providing second-site backup, identifying critical applications, performing backup and off-site storage procedures, creating a disaster recovery team, and testing the DRP.

PROVIDING SECOND-SITE BACKUP

A necessary ingredient in a DRP is that it provides for duplicate data processing facilities following a dis- aster. The viable options available include the empty shell, recovery operations center, and internally pro- vided backup.

The Empty Shell

The empty shell or cold site plan is an arrangement wherein the company buys or leases a building that will serve as a data center. In the event of a disaster, the shell is available and ready to receive whatever hardware the temporary user needs to run essential systems. This approach, however, has a fundamental weakness. Recovery depends on the timely availability of the necessary computer hardware to restore the data processing function. Management must obtain assurances (contracts) from hardware vendors that in the event of a disaster, the vendor will give the company’s needs priority. An unanticipated hardware sup- ply problem at this critical juncture could be a fatal blow.

The Recovery Operations Center

A recovery operations center (ROC) or hot site is a fully equipped backup data center that many companies share. In addition to hardware and backup facilities, ROC service providers offer a range of technical services to their clients, who pay an annual fee for access rights. In the event of a major disaster, a sub- scriber can occupy the premises and, within a few hours, resume processing critical applications.

September 11, 2001, was a true test of the reliability and effectiveness of the ROC approach. Com- disco, a major ROC provider, had 47 clients who declared 93 separate disasters on the day of the attack. All 47 companies relocated and worked out of Comdisco’s recovery centers. At one point, 3,000 client employees were working out of the centers. Thousands of computers were configured for clients’ needs within the first 24 hours, and systems recovery teams were on-site wherever police permitted access. By September 25, nearly half of the clients were able to return to their facilities with a fully functional system.

A problem with this approach is the potential for competition among users for the ROC resources. A widespread natural disaster, such as a flood or an earthquake, may destroy the data processing capabilities of several ROC members located in the same geographic area. All the victims will find themselves vying for access to the same limited facilities. Because some ROC service providers oversell their capacity by a ratio of 20:1, the situation is analogous to a sinking ship that has an inadequate number of lifeboats.

The period of confusion following a disaster is not an ideal time to negotiate property rights. There- fore, before entering into an ROC arrangement, management should consider the potential problems of overcrowding and geographic clustering of the current membership.

Internally Provided Backup

Larger organizations with multiple data processing centers often prefer the self-reliance that creating internal excess capacity provides. This permits firms to develop standardized hardware and software con- figurations, which ensure functional compatibility among their data processing centers and minimize cutover problems in the event of a disaster.

Pershing, a division of Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette Securities Corporation, processes more than 36 million transactions per day, about 2,000 per second. Pershing management recognized that an ROC vendor could not provide the recovery time they wanted and needed. The company, therefore, built its own remote mirrored data center. The facility is equipped with high-capacity storage devices capable of storing more than 20 terabytes of data and two IBM mainframes running high-speed copy software. All transactions that the main system processes are transmitted in real time along fiber-optic cables to the remote backup facility. At any point in time, the mirrored data center reflects current economic events of the firm. The mirrored system has reduced Pershing’s data recovery time from 24 hours to 1 hour.

IDENTIFYING CRITICAL APPLICATIONS

Another essential element of a DRP involves procedures to identify the critical applications and data files of the firm to be restored. Eventually, all applications and data must be restored to predisaster business activity levels. Immediate recovery efforts, however, should focus on restoring those applications and data that are critical to the organization’s short-run survival. In any disaster scenario, it is short-term survivability that determines long-term survival.

For most organizations, short-term survival requires the restoration of those functions that generate cash flows sufficient to satisfy short-term obligations. For example, assume that the following functions affect the cash flow position of a particular firm:

• Customer sales and service

• Fulfillment of legal obligations

• Accounts receivable maintenance and collection

• Production and distribution

• Purchasing

• Communications between branches or agencies

• Public relations

The computer applications that support these functions directly are critical. Hence, these applications should be so identified and prioritized in the restoration plan.

Application priorities may change over time, and these decisions must be reassessed regularly. Systems are constantly revised and expanded to reflect changes in user requirements. Similarly, the DRP must be updated to reflect new developments and identify critical applications. Up-to-date priorities are important because they affect other aspects of the strategic plan. For example, changes in application priorities may cause changes in the nature and extent of second-site backup requirements and specific backup procedures.

The task of identifying and prioritizing critical applications requires the active participation of management, user departments, and internal auditors. Too often, this task is incorrectly perceived to be an IT issue and delegated to IT professionals. Although the technical assistance of systems personnel is required, this is primarily a business decision and those best equipped to understand the business problem should make it.

PERFORMING BACKUP AND OFF-SITE STORAGE PROCEDURES

All data files, application documentation, and supplies needed to perform critical functions should be specified in the DRP. Data processing personnel should routinely perform backup and storage procedures to safeguard these critical resources.

Backup Data Files

The state-of-the-art in database backup is the remote mirrored site, described previously, which pro- vides complete data currency. Not all organizations are willing or able to invest in such backup resources. As a minimum, however, databases should be copied daily to tape or disks and secured off- site. In the event of a disruption, reconstruction of the database is achieved by updating the most current backup version with subsequent transaction data. Likewise, master files and transaction files should be protected.

Backup Documentation

The system documentation for critical applications should be backed up and stored off-site in much the same manner as data files. The large volumes of material involved and constant application revisions complicate the task. The process can be made more efficient through the use of computer-aided software engineering (CASE) documentation tools.

Backup Supplies and Source Documents

The firm should maintain backup inventories of supplies and source documents used in the critical applications. Examples of critical supplies are check stocks, invoices, purchase orders, and any other special- purpose forms that cannot be obtained immediately.

CREATING A DISASTER RECOVERY TEAM

Recovering from a disaster depends on timely corrective action. Failure to perform essential tasks (such as obtaining backup files for critical applications) prolongs the recovery period and diminishes the prospects for a successful recovery. To avoid serious omissions or duplication of efforts during implementation of the contingency plan, individual task responsibility must be clearly defined and communicated to the personnel involved.

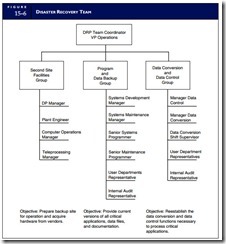

Figure 15-6 presents an organizational chart depicting the possible composition of a disaster recovery team. The team members should be experts in their areas and have assigned tasks. Following a disaster,

team members will delegate subtasks to their subordinates. It should be noted that traditional control concerns do not apply in this setting. The environment the disaster creates may necessitate the breaching of normal controls such as segregation of duties, access controls, and supervision. At this point, business continuity is the primary consideration.

TESTING THE DRP

The most neglected aspect of contingency planning is testing the plans. Nevertheless, DRP tests are important and should be performed periodically. Tests provide measures of the preparedness of personnel and identify omissions or bottlenecks in the plan.

A test is most useful in the form of a surprise simulation of a disruption. When the mock disaster is announced, the status of all processing that it affects should be documented. This provides a benchmark for subsequent performance assessments. The plan should be carried as far as is economically feasible. Ideally, this will include the use of backup facilities and supplies.

AUDIT OBJECTIVE: ASSESSING DISASTER RECOVERY PLANNING

The auditor should verify that management’s disaster recovery plan is adequate and feasible for dealing with a catastrophe that could deprive the organization of its computing resources. The following tests focus on the areas of greatest concern.

AUDIT PROCEDURES FOR ASSESSING DISASTER RECOVERY PLANNING

Second-Site Backup

The auditor should evaluate the adequacy of the backup site arrangement. The client should possess vendor contracts guaranteeing timely equipment delivery to the cold site. In the case of ROC membership, the auditor should obtain information as to the total number of members and their geographic dispersion. A widespread disaster may create a demand that the backup facility cannot satisfy.

Critical Application List

The auditor should review the list of critical applications and ensure that it is current and complete. Missing applications may result in failure to recover. On the other hand, restoring noncritical applications diverts scarce resources to nonproductive tasks.

Backup Critical Applications and Critical Data Files

The auditor should verify that the organization has procedures in place to back up stored off-site copies of critical applications and data. Evidence of this can be obtained by selecting a sample of data files and programs and determine if they are being backed up as required.

Backup Supplies, Source Documents, and Documentation

The system documentation, supplies, and source documents needed to restore and run critical applications should be backed up and stored off-site. The auditor should verify that the types and quantities of items specified in the DRP exist in a secure location.

The Disaster Recovery Team

The DRP should clearly list the names, addresses, and emergency telephone numbers of the disaster recovery team members. The auditor should verify that members of the team are current employees and are aware of their assigned responsibilities. On one occasion, while reviewing a firm’s DRP, the author dis- covered that a team leader listed in the plan had been deceased for 9 months.

Comments

Post a Comment