The Revenue Cycle:The Conceptual System

The Revenue Cycle

Economic enterprises, both for-profit and not-for- profit, generate revenues through business processes that constitute their revenue cycle. In its simplest form, the revenue cycle is the direct exchange of finished goods or services for cash in a single transaction between a seller and a buyer. More complex revenue cycles process sales on credit. Many days or weeks may pass between the point of sale and the subsequent receipt of cash. This time lag splits the revenue transaction into two phases: (1) the physical phase, involving the transfer of assets or services from the seller to the buyer; and (2) the financial phase, involving the receipt of cash by the seller in payment of the account receivable. As a matter of processing convenience, most firms treat each phase as a separate transaction. Hence, the revenue cycle actually consists of two major subsystems: (1) the sales order processing subsystem and (2) the cash receipts subsystem.

This chapter is organized into two main sections. The first section presents the conceptual revenue cycle system. It provides an overview of key activities and the logical tasks, sources and uses of information, and movement of accounting information through the organization. The section concludes with a review of internal control issues. The second section presents the physical system. A manual system is first used to reinforce key concepts previously presented. Next, it explores large-scale computer-based systems. The focus is on alternative technologies used to achieve various levels of organizational change from simple automation to reengineering the work flow. The section concludes with a review of personal computer (PC)-based systems and control issues pertaining to end-user computing.

The Conceptual System

OVERVIEW OF REVENUE CYCLE ACTIVITIES

In this section we examine the revenue cycle conceptually. Using data flow diagrams (DFDs) as a guide, we will trace the sequence of activities through three processes that constitute the revenue cycle for most retail, wholesale, and manufacturing organizations. These are sales order procedures, sales return procedures, and cash receipts procedures. Service companies such as hospitals, insurance companies, and banks would use different industry-specific methods.

This discussion is intended to be technology-neutral. In other words, the tasks described may be performed manually or by computer. At this point our focus is on what (conceptually) needs to be done, not how (physically) it is accomplished. At various stages in the processes we will examine specific documents, journals, and ledgers as they are encountered. Again, this review is technology-neutral. These documents and files may be physical (hard copy) or digital (computer-generated). In the next section, we examine examples of physical systems.

Sales Order Procedures

Sales order procedures include the tasks involved in receiving and processing a customer order, filling the order and shipping products to the customer, billing the customer at the proper time, and correctly accounting for the transaction. The relationships between these tasks are presented with the DFD in Figure 4-1 and described in the following section.

RECEIVE ORDER. The sales process begins with the receipt of a customer order indicating the type and quantity of merchandise desired. At this point, the customer order is not in a standard format and may or may not be a physical document. Orders may arrive by mail, by telephone, or from a field representative who visited the customer. When the customer is also a business entity, the order is often a copy of the customer’s purchase order. A purchase order is an expenditure cycle document, which is discussed in Chapter 5.

Because the customer order is not in the standard format that the seller’s order processing system needs, the first task is to transcribe it into a formal sales order, an example of which is presented in Figure 4-2.

The sales order captures vital information such as the customer’s name, address, and account number; the name, number, and description of the items sold; and the quantities and unit prices of each item sold. At this point, financial information such as taxes, discounts, and freight charges may or may not be included. After creating the sales order, a copy of it is placed in the customer open order file for future reference. The task of filling an order and getting the product to the customer may take days or even weeks. During this period, customers may contact their suppliers to check the status of their orders. The customer record in the open order file is updated each time the status of the order changes such as credit approval, on back-order, and shipment. The open order file thus enables customer service employees to respond promptly and accurately to customer questions.

CHECK CREDIT. Before processing the order further, the customer’s creditworthiness needs to be established. The circumstances of the sale will determine the nature and degree of the credit check. For example, new customers may undergo a full financial investigation to establish a line of credit. Once a credit limit is set, however, credit checking on subsequent sales may be limited to ensuring that the customer has a history of paying his or her bills and that the current sale does not exceed the pre-established limit.

The credit approval process is an authorization control and should be performed as a function separate from the sales activity. In our conceptual system, the receive-order task sends the sales order (credit copy) to the check-credit task for approval. The returned approved sales order then triggers the continuation of the sales process by releasing sales order information simultaneously to various tasks. Several documents mentioned in the following sections, such as the stock release, packing slip, shipping notice, and sales invoice, are simply special-purpose copies of the sales order and are not illustrated separately.

PICK GOODS. The receive order activity forwards the stock release document (also called the picking ticket) to the pick goods function, in the warehouse. This document identifies the items of inventory that

must be located and picked from the warehouse shelves. It also provides formal authorization for ware- house personnel to release the specified items. After picking the stock, the order is verified for accuracy and the goods and verified stock release document are sent to the ship goods task. If inventory levels are insufficient to fill the order, a warehouse employee adjusts the verified stock release to reflect the amount actually going to the customer. The employee then prepares a back-order record, which stays on file until the inventories arrive from the supplier (not shown in Figure 4-1). Back-ordered items are shipped before new sales are processed.

Finally, the warehouse employee adjusts the stock records to reflect the reduction in inventory. These stock records are not the formal accounting records for controlling inventory assets. They are used for warehouse management purposes only. Assigning asset custody and accounting record-keeping responsibility to the warehouse clerk would violate a key principle of internal control. The inventory control function, discussed later, maintains the formal accounting inventory records.

SHIP GOODS. Before the arrival of the goods and the verified stock release document, the shipping department receives the packing slip and shipping notice from the receive order function. The packing slip will ultimately travel with the goods to the customer to describe the contents of the order. The ship- ping notice will later be forwarded to the billing function as evidence that the customer’s order was filled and shipped. This document conveys pertinent new facts such as the date of shipment, the items and quantities actually shipped, the name of the carrier, and freight charges. In some systems, the shipping notice is a separate document prepared within the shipping function.

Upon receiving the goods from the warehouse, the shipping clerk reconciles the physical items with the stock release, the packing slip, and the shipping notice to verify that the order is correct. The ship goods function thus serves as an important independent verification control point and is the last opportunity to detect errors before shipment. The shipping clerk packages the goods, attaches the packing slip, completes the shipping notice, and prepares a bill of lading. The bill of lading, as shown in Figure 4-3, is a formal contract between the seller and the shipping company (carrier) to transport the goods to the customer. This document establishes legal ownership and responsibility for assets in transit. Once the goods are transferred to the carrier, the shipping clerk records the shipment in the shipping log, forwards the shipping notice and the stock release to the bill-customer function as proof of shipment, and updates the customer’s open order file.

BILL CUSTOMER. The shipment of goods marks the completion of the economic event and the point at which the customer should be billed. Billing before shipment encourages inaccurate record keeping and inefficient operations. When the customer order is originally prepared, some details such as inventory availability, prices, and shipping charges may not be known with certainty. In the case of back-orders, for example, suppliers do not typically bill customers for out-of-stock items. Billing for goods not shipped causes confusion, damages relations with customers, and requires additional work to make adjustments to the accounting records.

To prevent such problems, the billing function awaits notification from shipping before it bills. Figure 4-1 shows that upon credit approval, the bill-customer function receives the sales order (invoice copy) from the receive order task. This document is placed in an S.O. pending file until receipt of the shipping notice, which describes the products that were actually shipped to the customer. Upon arrival, the items shipped are reconciled with those ordered and unit prices, taxes, and freight charges are added to the invoice copy of the sales order. The completed sales invoice is the customer’s bill, which formally depicts the charges to the customer. In addition, the billing function performs the following record keeping–related tasks:

• Records the sale in the sales journal.

• Forwards the ledger copy of the sales order to the update accounts receivable task.

• Sends the stock release document to the update inventory records task.

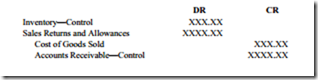

The sales journal is a special journal used for recording completed sales transactions. The details of sales invoices are entered in the journal individually. At the end of the period, these entries are summarized into a sales journal voucher, which is sent to the general ledger task for posting to the following accounts:

Figure 4-4 illustrates a journal voucher. Each journal voucher represents a general journal entry and indicates the general ledger accounts affected. Summaries of transactions, adjusting entries, and closing entries are all entered into the general ledger via this method. When properly approved, journal vouchers are an effective control against unauthorized entries to the general ledger. The journal voucher system eliminates the need for a formal general journal, which is replaced by a journal voucher file.

UPDATE INVENTORY RECORDS. The inventory control function updates inventory subsidiary ledger accounts from information contained in the stock release document. In a perpetual inventory system, every inventory item has its own record in the ledger containing, at a minimum, the data depicted

in Figure 4-5. Each stock release document reduces the quantity on hand of one or more inventory accounts. Periodically, the financial value of the total reduction in inventory is summarized in a journal voucher and sent to the general ledger function for posting to the following accounts:

UPDATE ACCOUNTS RECEIVABLE. Customer records in the accounts receivable (AR) subsidiary ledger are updated from information the sales order (ledger copy) provides. Every customer has an account record in the AR subsidiary ledger containing, at minimum, the following data: customer name; customer address; current balance; available credit; transaction dates; invoice numbers; and credits for payments, returns, and allowances. Figure 4-6 presents an example of an AR subsidiary ledger record.

Periodically, the individual account balances are summarized in a report that is sent to the general ledger. The purpose for this is discussed next.

POST TO GENERAL LEDGER. By the close of the transaction processing period, the general ledger function has received journal vouchers from the billing and inventory control tasks and an account summary from the AR function. This information set serves two purposes. First, the general ledger uses the journal vouchers to post to the following control accounts:

Because general ledger accounts are used to prepare financial statements, they contain only summary figures (no supporting detail) and require only summary posting information. Second, this information supports an important independent verification control. The AR summary, which the AR function independently provides, is used to verify the accuracy of the journal vouchers from billing. The AR summary figures should equal the total debits to AR reflected in the journal vouchers for the transaction period. By reconciling these figures, the general ledger function can detect many types of errors. We examine this point more fully in a later section dealing with revenue cycle controls.

SALES RETURN PROCEDURES

An organization can expect that a certain percentage of its sales will be returned. This occurs for a number of reasons, some of which may be:

• The company shipped the customer the wrong merchandise.

• The goods were defective.

• The product was damaged in shipment.

• The buyer refused delivery because the seller shipped the goods too late or they were delayed in transit.

When a return is necessary, the buyer requests credit for the unwanted products. This involves revers- ing the previous transaction in the sales order procedure. Using the DFD in Figure 4-7, let’s now review the procedures for approving and processing returned items.

PREPARE RETURN SLIP. When items are returned, the receiving department employee counts, inspects, and prepares a return slip describing the items. The goods, along with a copy of the return slip, go to the warehouse to be restocked. The employee then sends the second copy of the return slip to the sales function to prepare a credit memo.

PREPARE CREDIT MEMO. Upon receipt of the return slip, the sales employee prepares a credit memo. This document is the authorization for the customer to receive credit for the merchandise returned. Note that the credit memo illustrated in Figure 4-8 is similar in appearance to a sales order. Some systems may actually use a copy of the sales order marked credit memo.

In cases in which specific authorization is required (that is, the amount of the return or circumstances surrounding the return exceed the sales employee’s general authority to approve), the credit memo goes to the credit manager for approval. However, if the clerk has sufficient general authority to approve the return, the credit memo is sent directly to the billing function, where the customer sales transaction is reversed.

APPROVE CREDIT MEMO. The credit manager evaluates the circumstances of the return and makes a judgment to grant (or disapprove) credit. The manager then returns the approved credit memo to the sales department.

UPDATE SALES JOURNAL. Upon receipt of the approved credit memo, the transaction is recorded in the sales journal as a contra entry. The credit memo is then forwarded to the inventory control function for posting. At the end of the period, total sales returns are summarized in a journal voucher and sent to the general ledger department.

UPDATE INVENTORY AND AR RECORDS. The inventory control function adjusts the inventory records and forwards the credit memo to accounts receivable, where the customer’s account is also adjusted. Periodically, inventory control sends a journal voucher summarizing the total value of inventory returns to the general ledger update task. Similarly, accounts receivable submits an AR account summary to the general ledger function.

UPDATE GENERAL LEDGER. Upon receipt of the journal voucher and account summary information, the general ledger function reconciles the figures and posts to the following control accounts:

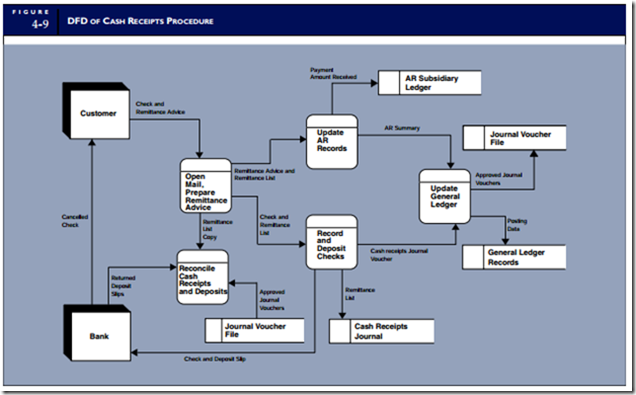

The sales order procedure described a credit transaction that resulted in the establishment of an account receivable. Payment on the account is due at some future date, which the terms of trade determine. Cash receipts procedures apply to this future event. They involve receiving and securing the cash; depositing the cash in the bank; matching the payment with the customer and adjusting the correct account; and properly accounting for and reconciling the financial details of the transaction. The DFD in Figure 4-9 shows the relationship between these tasks. They are described in detail in the following section.

OPEN MAIL AND PREPARE REMITTANCE ADVICE. A mail room employee opens envelopes containing customers’ payments and remittance advices. Remittance advices (see Figure 4-10) contain in- formation needed to service individual customers’ accounts. This includes payment date, account number, amount paid, and customer check number. Only the portion above the perforated line is the remittance advice, which the customer removes and returns with the payment. In some systems, the lower portion of the document is a customer statement that the billing department sends out periodically. In other cases, this could be the original customer invoice, which was described in the sales order procedures.

The remittance advice is a form of a turnaround document, as described in Chapter 2. Its importance is most apparent in firms that process large volumes of cash receipts daily. For example, processing a check from John Smith with no supporting details would require a time-consuming and costly search through perhaps thousands of records to find the correct John Smith. This task is greatly simplified when the customer provides necessary account number and posting information. Because of the possibility of transcription errors and omissions, however, sellers do not rely on their customers to provide this information directly on their checks. Errors are avoided and operational efficiency is greatly improved when using remittance advices.

Mail room personnel route the checks and remittance advices to an administrative clerk who endorses the checks ‘‘For Deposit Only’’ and reconciles the amount on each remittance advice with the corresponding check. The clerk then records each check on a form called a remittance list (or cash prelist), where all cash received is logged. In this example, the clerk prepares three copies of the remittance list. The original copy is sent with the checks to the record and deposit checks function. The second copy goes with the remittance advices to the update AR function. The third goes to a reconciliation task.

RECORD AND DEPOSIT CHECKS. A cash receipts employee verifies the accuracy and complete- ness of the checks against the prelist. Any checks possibly lost or misdirected between the mail room and

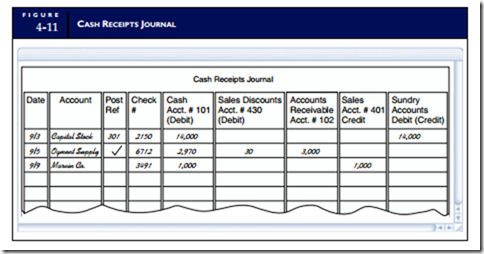

this function are thus identified. After reconciling the prelist to the checks, the employee records the check in the cash receipts journal. All cash receipts transactions, including cash sales, miscellaneous cash receipts, and cash received on account, are recorded in the cash receipts journal. Figure 4-11 illustrates this with an example of each type of transaction. Notice that each check received from a customer is listed as a separate line item.

Next, the clerk prepares a bank deposit slip showing the amount of the day’s receipts and forwards this along with the checks to the bank. Upon deposit of the funds, the bank teller validates the deposit slip and returns it to the company for reconciliation. At the end of the day, the cash receipts employee summa- rizes the journal entries and sends the following journal voucher entry to the general ledger function.

UPDATE ACCOUNTS RECEIVABLE. The remittance advices are used to post to the customers’ accounts in the AR subsidiary ledger. Periodically, the changes in account balances are summarized and forwarded to the general ledger function.

UPDATE GENERAL LEDGER. Upon receipt of the journal voucher and the account summary, the general ledger function reconciles the figures, posts to the cash and AR control accounts, and files the journal voucher.

RECONCILE CASH RECEIPTS AND DEPOSITS. Periodically (weekly or monthly), a clerk from the controller’s office (or an employee not involved with the cash receipts procedures) reconciles cash receipts by comparing the following documents: (1) a copy of the prelist, (2) deposit slips received from the bank, and (3) related journal vouchers.

REVENUE CYCLE CONTROLS

Chapter 3 defined six classes of internal control activities that guide us in designing and evaluating trans- action processing controls. They are transaction authorization, segregation of duties, supervision, accounting records, access control, and independent verification. Table 4-1 summarizes these control activities as they apply in the revenue cycle.

Transaction Authorization

The objective of transaction authorization is to ensure that only valid transactions are processed. In the following sections, we see how this objective applies in each of the three systems.

CREDIT CHECK. Credit checking of prospective customers is a credit department function. This department ensures the proper application of the firm’s credit policies. The principal concern is the credit- worthiness of the customer. In making this judgment, the credit department may employ various techniques and tests. The complexity of credit procedures will vary depending on the organization, its relationship with the customer, and the materiality of the transaction. Credit approval for first-time customers may take time. Credit decisions that fall within a sales employee’s general authority (such as verifying that the current transaction does not exceed the customer’s credit limit) may be dealt with very quickly. Whatever level of test is deemed necessary by company policy, the transaction should not proceed further until credit is approved.

RETURN POLICY. Because credit approval is generally a credit department function, that department authorizes the processing of sales returns as well. An approval determination is based on the nature of the sale and the circumstances of the return. The concepts of specific and general authority also influence this activity. Most organizations have specific rules for granting cash refunds and cred- its to customers based on the materiality of the transaction. As materiality increases, credit approval becomes more formal.

REMITTANCE LIST (CASH PRELIST). The cash prelist provides a means for verifying that customer checks and remittance advices match in amount. The presence of an extra remittance advice in the AR department or the absence of a customer’s check in the cash receipts department would be detected when the batch is reconciled with the prelist. Thus, the prelist authorizes the posting of a remittance advice to a customer’s account.

168 P A R T I I Transaction Cycles and Business Processes

Segregation of Duties

Segregating duties ensures that no single individual or department processes a transaction in its entirety. The number of employees and the volume of transactions being processed influence how to accomplish the segregation. Recall from Chapter 3 that three rules guide systems designers in this task:

1. Transaction authorization should be separate from transaction processing.

Within the revenue cycle, the credit department is segregated from the rest of the process, so formal authorization of a transaction is an independent event. The importance of this separation is clear when one considers the potential conflict in objectives between the individual salesperson and the organization. Often, compensation for sales staff is based on their individual sales performance. In such cases, sales staff have an incentive to maximize sales volume and thus may not adequately consider the creditworthiness of prospective customers. By acting in an independent capacity, the credit department may objectively detect risky customers and disallow poor and irresponsible sales decisions.

2. Asset custody should be separate from the task of asset record keeping.

The physical assets at risk in the revenue cycle are inventory and cash, hence the need to separate asset custody from record keeping. The inventory warehouse has physical custody of inventory assets, but inventory control (an accounting function) maintains records of inventory levels. To combine these tasks would open the door to fraud and material errors. A person with combined responsibility could steal or lose inventory and adjust the inventory records to conceal the event.

Similarly, the cash receipts department takes custody of the cash asset, while updating AR records is an accounts receivable (accounting function) responsibility. The cash receipts department typically reports to the treasurer, who has responsibility for financial assets. Accounting functions report to the controller. Normally these two general areas of responsibility are performed independently.

3. The organization should be structured so that the perpetration of a fraud requires collusion between two or more individuals.

The record-keeping tasks need to be carefully separated. Specifically, the subsidiary ledgers (AR and inventory), the journals (sales and cash receipts), and the general ledger should be separately maintained. An individual with total record-keeping responsibility, in collusion with someone with asset custody, is in a position to perpetrate fraud. By separating these tasks, collusion must involve more people, which increases the risk of detection and therefore is less likely to occur.

Supervision

Some firms have too few employees to achieve an adequate separation of functions. These firms must rely on supervision as a form of compensating control. By closely supervising employees who perform potentially incompatible functions, a firm can compensate for this exposure.

Supervision can also provide control in systems that are properly segregated. For example, the mail room is a point of risk in most cash receipts systems. The individual who opens the mail has access both to cash (the asset) and to the remittance advice (the record of the transaction). A dishonest employee may use this opportunity to steal the check, cash it, and destroy the remittance advice, thus leaving no evidence of the transaction. Ultimately, this sort of fraud will come to light when the customer complains after being billed again for the same item and produces the canceled check to prove that payment was made. By the time the firm gets to the bottom of this problem, however, the perpetrator may have committed the crime many times and left the organization. Detecting crimes after the fact accomplishes little; prevention is the best solution. The deterrent effect of supervision can provide an effective preventive control.

Accounting Records

Chapter 2 described how a firm’s source documents, journals, and ledgers form an audit trail that allows independent auditors to trace transactions through various stages of processing. This control is also an important operational feature of well-designed accounting systems. Sometimes transactions get lost in the system. By following the audit trail, management can discover where an error occurred. Several specific control techniques contribute to the audit trail.

PRENUMBERED DOCUMENTS. Prenumbered documents (sales orders, shipping notices, remittance advices, and so on) are sequentially numbered by the printer and allow every transaction to be identified uniquely. This permits the isolation and tracking of a single event (among many thousands) through the accounting system. Without a unique tag, one transaction looks very much like another. Verifying financial data and tracing transactions would be difficult or even impossible without prenumbered source documents.

SPECIAL JOURNALS. By grouping similar transactions together into special journals, the system pro- vides a concise record of an entire class of events. For this purpose, revenue cycle systems use the sales journal and the cash receipts journal.

SUBSIDIARY LEDGERS. Two subsidiary ledgers are used for capturing transaction event details in the revenue cycle: the inventory and AR subsidiary ledgers. The sale of products reduces quantities on hand in the inventory subsidiary records and increases the customers’ balances in the AR subsidiary records. The receipt of cash reduces customers’ balances in the AR subsidiary records. These subsidiary records provide links back to journal entries and to the source documents that captured the events.

GENERAL LEDGERS. The general ledger control accounts are the basis for financial statement preparation. Revenue cycle transactions affect the following general ledger accounts: sales, inventory, cost of goods sold, AR, and cash. Journal vouchers that summarize activity captured in journals and subsidiary ledgers flow into the general ledger to update these accounts. Thus we have a complete audit trail from the financial statements to the source documents via the general ledger, subsidiary ledgers, and special journals.

FILES. The revenue cycle employs several temporary and permanent files that contribute to the audit trail. The following are typical examples:

• Open sales order file shows the status of customer orders.

• Shipping log specifies orders shipped during the period.

• Credit records file provides customer credit data.

• Sales order pending file contains open orders not yet shipped or billed.

• Back-order file contains customer orders for out-of-stock items.

• Journal voucher file is a compilation of all journal vouchers posted to the general ledger.

Access Controls

Access controls prevent and detect unauthorized and illegal access to the firm’s assets. The physical assets at risk in the revenue cycle are inventories and cash. Limiting access to these items includes:

• Warehouse security, such as fences, alarms, and guards.

• Depositing cash daily in the bank.

• Using a safe or night deposit box for cash.

• Locking cash drawers and safes in the cash receipts department.

Information is also an important asset at risk. Access control over information involves restricting access to documents that control physical assets including source documents, journals, and ledgers. An individual with unrestricted access to records can effectively manipulate the physical assets of the firm. The following are examples of access risks in the revenue cycle:

1. An individual with access to the AR subsidiary ledger could remove his or her account (or someone else’s) from the books. With no record of the account, the firm would not send the customer monthly statements.

170 P A R T I I Transaction Cycles and Business Processes

2. Access to sales order documents may permit an unauthorized individual to trigger the shipment of a product.

3. An individual with access to both cash and the general ledger cash account could remove cash from the firm and adjust the cash account to cover the act.

Independent Verification

The objective of independent verification is to verify the accuracy and completeness of tasks that other functions in the process perform. To be effective, independent verifications must occur at key points in the process where errors can be detected quickly and corrected. Independent verification controls in the revenue cycle exist at the following points:

1. The shipping function verifies that the goods sent from the warehouse are correct in type and quantity. Before the goods are sent to the customer, the stock release document and the packing slip are reconciled.

2. The billing function reconciles the original sales order with the shipping notice to ensure that custom- ers are billed for only the quantities shipped.

3. Prior to posting to control accounts, the general ledger function reconciles journal vouchers and summary reports prepared independently in different function areas. The billing function summarizes the sales journal, inventory control summarizes changes in the inventory subsidiary ledger, the cash receipts function summarizes the cash receipts journal, and accounts receivable summarizes the AR subsidiary ledger.

Discrepancies between the numbers supplied by these various sources will signal errors that need to be resolved before posting to the general ledger can take place. For example, the general ledger function would detect a sales transaction that had been entered in the sales journal but not posted to the customer’s account in the AR subsidiary ledger. The journal voucher from billing, summarizing total credit sales, would not equal the total increases posted to the AR subsidiary ledger. The specific customer account causing the out-of-balance condition would not be determinable at this point, but the error would be noted. Finding it may require examining all the transactions processed during the period. Depending on the technology in place, this could be a tedious task.

Comments

Post a Comment