Internal Control Cases

Internal Control Cases

1. Bern Fly Rod Company

Bern Fly Rod Company is a small manufacturer of high- quality graphite fly-fishing rods. It sells its products to fly-fishing shops throughout the United States and Canada. Bern began as a small company with four salespeople, all family members of the owner. Because of the high popularity and recent growth of fly-fishing, Bern now employs a seasonal, nonfamily, sales force of 16. The salespeople travel around the country giving fly- casting demonstrations of their new models to fly-fishing shops. When the fishing season ends in October, the temporary salespeople are laid off until the following spring.

Once the salesperson takes an order, it is sent directly to the cash disbursement department, where commission is calculated and promptly paid. Sales staff compensation is tied directly to their sales (orders taken) figures. The order is then sent to the billing department, where the sale is recorded, and finally to the shipping department for delivery to the customer. Sales staff are also compensated for travel expenses. Each week they submit a hard-copy spreadsheet of expenses incurred to the cash disbursements clerk. The clerk immediately writes a check to the salesperson for the amount indicated in the spreadsheet.

Bern’s financial statements for the December year- end reflect an unprecedented jump in sales for the month of October (35 percent higher than the same period in the previous year). On the other hand, the statements show a high rate of product returns in the months of November and December, which virtually offset the jump in sales. Furthermore, travel expenses for the period ending October 31 were disproportionately high compared with previous months.

Required

Analyze Bern’s situation and assess any potential inter- nal control issues and exposures. Discuss some preven- tive measures this firm may wish to implement.

2. Breezy Company

(This case was prepared by Elizabeth Morris, Lehigh University)

Breezy Company of Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, is a small wholesale distributor of heating and cooling fans. The company deals with retailing firms that buy small to medium quantities of fans. The president, Chuck Breezy, was very pleased with the marked increase in sales over the past couple of years. Recently, however, the accountant informed Chuck that although net income has increased, the percentage of uncollectibles has tripled. Because of the small size of the business, Chuck fears he may not be able to sustain these increased losses in the future. He asked his accountant to analyze the situation.

Background

In 1998, the sales manager, John Breezy, moved to Alaska, and Chuck hired a young college graduate to fill the posi- tion. The company had always been a family business and, therefore, measurements of individual performance had never been a large consideration. The sales levels had been relatively constant because John had been content to sell to certain customers with whom he had been dealing for years. Chuck was leery about hiring outside the family for this position. To try to keep sales levels up, he established a reward incentive based on net sales. The new sales man- ager, Bob Sellmore, was eager to set his career in motion and decided he would attempt to increase the sales levels. To do this, he recruited new customers while keeping the old clientele. After one year, Bob had proved himself to Chuck, who decided to introduce an advertising program to further increase sales. This brought in orders from a number of new customers, many of whom Breezy had never done business with before. The influx of orders excited Chuck so much that he instructed Jane Breezy, the finance manager, to raise the initial credit level for new customers. This induced some customers to purchase more.

Existing System

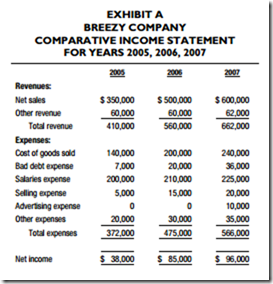

The accountant prepared a comparative income statement to show changes in revenues and expenses over the last three years, shown in Exhibit A. Currently, Bob is receiving a commission of 2 percent of net sales. Breezy Company uses credit terms of net 30 days. At the end of previous years, bad debt expense amounted to approximately 2 percent of net sales.

As the finance manager, Jane performs credit checks. In previous years, Jane had been familiar with most clients and approved credit on the basis of past behavior. When dealing with new customers, Jane usually approved a low credit amount and increased it after the customer exhibited reliability. With the large increase in sales, Chuck thought that the current policy was restricting a further rise in sales levels. He decided to increase credit limits to eliminate this restriction. This policy, combined with the new advertising program, should attract many new customers.

Future

The new level of sales impresses Chuck and he wishes to expand, but he also wants to keep uncollectibles to a minimum. He believes the amount of uncollectibles should remain relatively constant as a percentage of sales. Chuck is thinking of expanding his production line, but wants to see uncollectibles drop and sales stabilize before he proceeds with this plan.

Required

Analyze the weaknesses in internal control and suggest improvements.

3. Whodunit?

(This case was prepared by Karen Collins, Lehigh University)

The following facts relate to an actual embezzlement case.

Someone stole more than $40,000 from a small company in less than two months. Your job is to study the following facts, try to figure out who was responsible for the theft, how it was perpetrated, and (most important) suggest ways to prevent something like this from happening again.

Facts

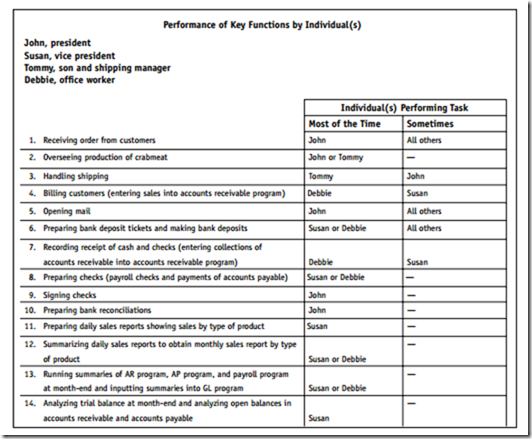

Location of company: a small town on the eastern shore of Maryland. Type of company: crabmeat processor, selling crabmeat to restaurants located in Maryland. Characters in the story (names are fictitious):

• John Smith, president and stockholder (husband of Susan).

• Susan Smith, vice president and stockholder (wife of John).

• Tommy Smith, shipping manager (son of John and Susan).

• Debbie Jones, office worker. She began working part-time for the company six months before the theft.

(At that time, she was a high school senior and was allowed to work afternoons through a school internship program.) Upon graduation from high school (several weeks before the theft was discovered), she began working full-time. Although she is not a member of the family, the Smiths have been close friends with Debbie’s parents for more than 10 years.

Accounting Records

All accounting records are maintained on a microcomputer. The software being used consists of the following modules:

1. A general ledger system, which keeps track of all balances in the general ledger accounts and produces a trial balance at the end of each month.

2. A purchases program, which keeps track of pur- chases and maintains detailed records of accounts payable.

3. An accounts receivable program, which keeps track of sales and collections on account and maintains individual detailed balances of accounts receivable.

4. A payroll program.

The modules are not integrated (that is, data are not transferred automatically between modules). At the end of the accounting period, summary information generated by the purchases, accounts receivable, and payroll programs must be entered into the general ledger pro- gram to update the accounts affected by these programs.

Sales

The crabmeat processing industry in this particular town was unusual in that selling prices for crabmeat were set at the beginning of the year and remained unchanged for the entire year. The company’s customers, all restaurants located within 100 miles of the plant, ordered the same quantity of crabmeat each week. Because prices for the crabmeat remained the same all year and the quantity ordered was always the same, the weekly invoice to each customer was always for the same dollar amount.

Manual sales invoices were produced when orders

were taken, although these manual invoices were not pre- numbered. One copy of the manual invoice was attached to the order shipped to the customer. The other copy was used to enter the sales information into the computer.

When the customer received the order, the customer would send a check to the company for the amount of the invoice. Monthly bills were not sent to customers unless the customer was behind in payments (that is, did not make a payment for the invoiced amount each week).

Note: The industry was unique in another way: many of the companies paid their workers with cash each week (rather than by check). Therefore, it was not un- usual for companies to request large sums of cash from the local banks.

When Trouble Was Spotted

Shortly after the May 30 trial balance was run, Susan began analyzing the balances in the various accounts. The balance in the cash account agreed with the cash balance she obtained from a reconciliation of the company’s bank account.

However, the balance in the accounts receivable control account in the general ledger did not agree with the total of the accounts receivable subsidiary ledger (which shows a detail of the balances owed by each customer). The difference was not very large, but the balances should be in 100 percent agreement.

At this point, Susan hired a fraud auditor to help her locate the problem. In reviewing the computerized accounts receivable subsidiary ledger, the auditor noticed the following:

1. The summary totals from this report were not the totals that were entered into the general ledger program at month-end. Different amounts had been entered. No one could explain why this had happened.

2. Some sheets in the computer listing had been ripped apart at the bottom. (In other words, the list- ing of the individual accounts receivable balances was not a continuous list but had been split at several points.)

3. When an adding machine tape of the individual account balances was run, the individual balances did not add up to the total at the bottom of the report.

Susan concluded that the accounts receivable program was not running properly. The auditor’s recommendation was that an effort be made to find out why the accounts receivable control account and the summary totals per the accounts receivable subsidiary ledger were not in agreement and why there were problems with the accounts receivable listing. Because the accounts receivable subsidiary and accounts receivable control account in the general ledger had been in agreement at the end of April, the effort should begin with the April ending balances for each customer by manually updating all of the accounts. The manually adjusted May 30 balances should then be compared with the computer-generated balances and any differences investigated.

After doing this, Susan and John found several differences. The largest difference was the following: Although they found the manual sales invoice for Sale 2, Susan and John concluded (based on the computer records) that Sale 2 did not take place. The auditor was not sure and recommended that they call this customer and ask him the following:

1. Did he receive this order?

2. Did he receive an invoice for it?

3. Did he pay for the order?

4. If so, did he have a copy of his canceled check?

Although John thought that this would be a waste of time, he called the customer. He received an affirmative answer to all of his questions. In addition, he found that the customer’s check was stamped on the back with an address stamp giving only the company’s name and city rather than the usual ‘‘for deposit only’’ company stamp. When questioned, Debbie said that she sometimes used this stamp.

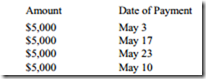

Right after this question, Debbie, who was sitting nearby at the computer, called Susan to the computer and showed her the customer’s account. She said that the payment for $5,000 was in fact recorded in the customer’s account. The payments were listed on the computer screen like this:

The auditor questioned the order of the payments—why was a check supposedly received on May 10 entered in the computer after checks received on May 17 and 23? About 30 seconds later, the computer malfunctioned and the accounts receivable file was lost. Every effort to retrieve the file gave the message ‘‘file not found.’’

About five minutes later, Debbie presented Susan with a copy of a bank deposit ticket dated May 10 with several checks listed on it, including the check that the customer said had been sent to the company. The de- posit ticket, however, was not stamped by the bank (which would have verified that the deposit had been received by the bank) and did not add up to the total at the bottom of the ticket (it was off by 20 cents).

At this point, being very suspicious, the auditor

gathered all of the documents he could and left the company to work on the problem at home, away from any potential suspects. He received a call from Susan about four hours later saying that she felt much better. She and Debbie had gone to RadioShack (the maker of their computer program) and RadioShack had con- firmed Susan’s conclusion that the computer program was malfunctioning. She and Debbie were planning to work all weekend reentering transactions into the computer. She said that everything looked fine and not to waste more time and expense working on the problem.

The auditor felt differently. How do you feel?

Comments

Post a Comment