Ethics, Fraud, and Internal Control:Internal Control Concepts and Techniques

Internal Control Concepts and Techniques

With a backdrop of ethics and fraud in place, let’s now examine internal control concepts and techniques for dealing with these problems. The internal control system comprises policies, practices, and procedures employed by the organization to achieve four broad objectives:

1. To safeguard assets of the firm.

2. To ensure the accuracy and reliability of accounting records and information.

3. To promote efficiency in the firm’s operations.

4. To measure compliance with management’s prescribed policies and procedures.16

Modifying Assumptions

Inherent in these control objectives are four modifying assumptions that guide designers and auditors of internal controls.17

MANAGEMENT RESPONSIBILITY. This concept holds that the establishment and maintenance of a system of internal control is a management responsibility. This point is made eminent in SOX legislation.

REASONABLE ASSURANCE. The internal control system should provide reasonable assurance that the four broad objectives of internal control are met in a cost-effective manner. This means that no system of internal control is perfect and the cost of achieving improved control should not outweigh its benefits.

METHODS OF DATA PROCESSING. Internal controls should achieve the four broad objectives regardless of the data processing method used. The control techniques used to achieve these objectives will, however, vary with different types of technology.

LIMITATIONS. Every system of internal control has limitations on its effectiveness. These include (1) the possibility of error—no system is perfect, (2) circumvention—personnel may circumvent the system through collusion or other means, (3) management override—management is in a position to override control procedures by personally distorting transactions or by directing a subordinate to do so, and (4) changing conditions—conditions may change over time so that existing controls may become ineffectual.

Exposures and Risk

Figure 3-2 portrays the internal control system as a shield that protects the firm’s assets from numerous undesirable events that bombard the organization. These include attempts at unauthorized access to the firm’s assets (including information); fraud perpetrated by persons both inside and outside the firm; errors due to employee incompetence, faulty computer programs, and corrupted input data; and mischievous acts, such as unauthorized access by computer hackers and threats from computer viruses that destroy programs and databases.

The absence or weakness of a control is called an exposure. Exposures, which are illustrated as holes in the control shield in Figure 3-2, increase the firm’s risk to financial loss or injury from undesirable events. A weakness in internal control may expose the firm to one or more of the following types of risks:

1. Destruction of assets (both physical assets and information).

2. Theft of assets.

3. Corruption of information or the information system.

4. Disruption of the information system.

The Preventive–Detective–Corrective Internal Control Model

Figure 3-3 illustrates that the internal control shield is composed of three levels of control: preventive controls, detective controls, and corrective controls. This is the preventive–detective–corrective (PDC) control model.

PREVENTIVE CONTROLS. Prevention is the first line of defense in the control structure. Preventive controls are passive techniques designed to reduce the frequency of occurrence of undesirable events. Preventive controls force compliance with prescribed or desired actions and thus screen out aberrant events. When designing internal control systems, an ounce of prevention is most certainly worth a pound of cure. Preventing errors and fraud is far more cost-effective than detecting and correcting problems after they occur. The vast majority of undesirable events can be blocked at this first level. For example, a well- designed source document is an example of a preventive control. The logical layout of the document into zones that contain specific data, such as customer name, address, items sold, and quantity, forces the clerk to enter the necessary data. The source documents can therefore prevent necessary data from being omit- ted. However, not all problems can be anticipated and prevented. Some will elude the most comprehen- sive network of preventive controls.

DETECTIVE CONTROLS. Detective controls form the second line of defense. These are devices, techniques, and procedures designed to identify and expose undesirable events that elude preventive controls. Detective controls reveal specific types of errors by comparing actual occurrences to pre-established standards. When the detective control identifies a departure from standard, it sounds an alarm to attract

attention to the problem. For example, assume a clerk entered the following data on a customer sales order:

| Quantity | Price | Total |

| 10 | $10 | $1,000 |

Before processing this transaction and posting to the accounts, a detective control should recalculate the total value using the price and quantity. Thus, the error in total price would be detected.

CORRECTIVE CONTROLS. Corrective controls are actions taken to reverse the effects of errors detected in the previous step. There is an important distinction between detective controls and corrective controls. Detective controls identify anomalies and draw attention to them; corrective controls actually fix the problem. For any detected error, however, there may be more than one feasible corrective action, but the best course of action may not always be obvious. For example, in viewing the error above, your first inclination may have been to change the total value from $1,000 to $100 to correct the problem. This presumes that the quantity and price values on the document are correct; they may not be. At this point, we cannot determine the real cause of the problem; we know only that one exists.

Linking a corrective action to a detected error, as an automatic response, may result in an incorrect action that causes a worse problem than the original error. For this reason, error correction should be viewed as a separate control step that should be taken cautiously.

The PDC control model is conceptually pleasing but offers little practical guidance for designing specific controls. For this, we need a more precise framework. The current authoritative document for specifying internal control objectives and techniques is Statement on Auditing Standards (SAS) No. 78,18 which is based on the COSO framework. We discuss the key elements of these documents in the following section.

Sarbanes-Oxley and Internal Control

Sarbanes-Oxley legislation requires management of public companies to implement an adequate system of internal controls over their financial reporting process. This includes controls over transaction processing systems that feed data to the financial reporting systems. Management’s responsibilities for this are codified in Sections 302 and 404 of SOX. Section 302 requires that corporate management (including the CEO) certify their organization’s internal controls on a quarterly and annual basis. In addition, Section 404 requires the management of public companies to assess the effectiveness of their organization’s inter- nal controls. This entails providing an annual report addressing the following points: (1) a statement of management’s responsibility for establishing and maintaining adequate internal control; (2) an assessment of the effectiveness of the company’s internal controls over financial reporting; (3) a statement that the organization’s external auditors have issued an attestation report on management’s assessment of the company’s internal controls; (4) an explicit written conclusion as to the effectiveness of internal control over financial reporting19; and (5) a statement identifying the framework used in their assessment of internal controls.

Regarding the control framework to be used, both the PCAOB and the SEC have endorsed the frame- work put forward by the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO). Further, they require that any other framework used should encompass all of COSO’s general themes.20 The COSO framework was the basis for SAS 78, but was designed as a management tool rather than an audit tool. SAS 78, on the other hand, was developed for auditors and describes the complex relationship between the firm’s internal controls, the auditor’s assessment of risk, and the planning of audit

procedures. Apart from their audience orientation, the two frameworks are essentially the same and inter- changeable for SOX compliance purposes. The key elements of the SAS 78/COSO framework are presented in the following section.

SAS 78/COSO INTERNAL CONTROL FRAMEWORK

The SAS 78/COSO framework consists of five components: the control environment, risk assessment, in- formation and communication, monitoring, and control activities.

The Control Environment

The control environment is the foundation for the other four control components. The control environ- ment sets the tone for the organization and influences the control awareness of its management and employees. Important elements of the control environment are:

• The integrity and ethical values of management.

• The structure of the organization.

• The participation of the organization’s board of directors and the audit committee, if one exists.

• Management’s philosophy and operating style.

• The procedures for delegating responsibility and authority.

• Management’s methods for assessing performance.

• External influences, such as examinations by regulatory agencies.

• The organization’s policies and practices for managing its human resources.

SAS 78/COSO requires that auditors obtain sufficient knowledge to assess the attitude and awareness of the organization’s management, board of directors, and owners regarding internal control. The follow- ing paragraphs provide examples of techniques that may be used to obtain an understanding of the control environment.

1. Auditors should assess the integrity of the organization’s management and may use investigative agencies to report on the backgrounds of key managers. Some of the ‘‘Big Four’’ public accounting firms employ former FBI agents whose primary responsibility is to perform background checks on existing and prospective clients. If cause for serious reservations comes to light about the integrity of the client, the auditor should withdraw from the audit. The reputation and integrity of the company’s managers are critical factors in determining the auditability of the organization. Auditors cannot func- tion properly in an environment in which client management is deemed unethical and corrupt.

2. Auditors should be aware of conditions that would predispose the management of an organization to commit fraud. Some of the obvious conditions may be lack of sufficient working capital, adverse industry conditions, bad credit ratings, and the existence of extremely restrictive conditions in bank or indenture agreements. If auditors encounter any such conditions, their examination should give due consideration to the possibility of fraudulent financial reporting. Appropriate measures should be taken, and every attempt should be made to uncover any fraud.

3. Auditors should understand a client’s business and industry and should be aware of conditions pecu- liar to the industry that may affect the audit. Auditors should read industry-related literature and fa- miliarize themselves with the risks that are inherent in the business.

4. The board of directors should adopt, as a minimum, the provisions of SOX. In addition, the following guidelines represent established best practices.

• Separate CEO and chairman. The roles of CEO and board chairman should be separate. Executive sessions give directors the opportunity to discuss issues without management present, and an independent chairman is important in facilitating such discussions.

• Set ethical standards. The board of directors should establish a code of ethical standards from which management and staff will take direction. At a minimum, a code of ethics should address such issues as outside employment conflicts, acceptance of gifts that could be construed as bribery, falsification of financial and/or performance data, conflicts of interest, political contributions, confidentiality of company and customer data, honesty in dealing with internal and external auditors, and membership on external boards of directors.

• Establish an independent audit committee. The audit committee is responsible for selecting and engaging an independent auditor, for ensuring that an annual audit is conducted, for reviewing the audit report, and for ensuring that deficiencies are addressed. Large organizations with complex accounting practices may need to create audit subcommittees that specialize in specific activities.

• Compensation committees. The compensation committee should not be a rubber stamp for man- agement. Excessive use of short-term stock options to compensate directors and executives may result in decisions that influence stock prices at the expense of the firm’s long-term health. Com- pensation schemes should be carefully evaluated to ensure that they create the desired incentives.

• Nominating committees. The board nominations committee should have a plan to maintain a fully staffed board of directors with capable people as it moves forward for the next several years. The committee must recognize the need for independent directors and have criteria for determining in- dependence. For example, under its newly implemented governance standards, General Electric (GE) considers directors independent if the sales to, and purchases from, GE total less than 1 per- cent of the revenue of the companies for which they serve as executives. Similar standards apply to charitable contributions from GE to any organization on which a GE director serves as officer or director. In addition, the company has set a goal that two-thirds of the board will be independent nonemployees.21

• Access to outside professionals. All committees of the board should have access to attorneys and con- sultants other than the corporation’s normal counsel and consultants. Under the provisions of SOX, the audit committee of an SEC reporting company is entitled to such representation independently.

Risk Assessment

Organizations must perform a risk assessment to identify, analyze, and manage risks relevant to financial reporting. Risks can arise or change from circumstances such as:

• Changes in the operating environment that impose new or changed competitive pressures on the firm.

• New personnel who have a different or inadequate understanding of internal control.

• New or reengineered information systems that affect transaction processing.

• Significant and rapid growth that strains existing internal controls.

• The implementation of new technology into the production process or information system that impacts transaction processing.

• The introduction of new product lines or activities with which the organization has little experience.

• Organizational restructuring resulting in the reduction and/or reallocation of personnel such that business operations and transaction processing are affected.

• Entering into foreign markets that may impact operations (that is, the risks associated with foreign cur- rency transactions).

• Adoption of a new accounting principle that impacts the preparation of financial statements.

SAS 78/COSO requires that auditors obtain sufficient knowledge of the organization’s risk assessment procedures to understand how management identifies, prioritizes, and manages the risks related to financial reporting.

Information and Communication

The accounting information system consists of the records and methods used to initiate, identify, analyze, classify, and record the organization’s transactions and to account for the related assets and liabilities.

The quality of information the accounting information system generates impacts management’s ability to take actions and make decisions in connection with the organization’s operations and to prepare reliable financial statements. An effective accounting information system will:

• Identify and record all valid financial transactions.

• Provide timely information about transactions in sufficient detail to permit proper classification and financial reporting.

• Accurately measure the financial value of transactions so their effects can be recorded in financial statements.

• Accurately record transactions in the time period in which they occurred.

SAS 78/COSO requires that auditors obtain sufficient knowledge of the organization’s information system to understand:

• The classes of transactions that are material to the financial statements and how those transactions are initiated.

• The accounting records and accounts that are used in the processing of material transactions.

• The transaction processing steps involved from the initiation of a transaction to its inclusion in the financial statements.

• The financial reporting process used to prepare financial statements, disclosures, and accounting estimates.

Monitoring

Management must determine that internal controls are functioning as intended. Monitoring is the process by which the quality of internal control design and operation can be assessed. This may be accomplished by separate procedures or by ongoing activities.

An organization’s internal auditors may monitor the entity’s activities in separate procedures. They gather evidence of control adequacy by testing controls and then communicate control strengths and weaknesses to management. As part of this process, internal auditors make specific recommendations for improvements to controls.

Ongoing monitoring may be achieved by integrating special computer modules into the information system that capture key data and/or permit tests of controls to be conducted as part of routine operations. Embedded modules thus allow management and auditors to maintain constant surveillance over the functioning of internal controls. In Chapter 17, we examine a number of embedded module techniques.

Another technique for achieving ongoing monitoring is the judicious use of management reports. Timely reports allow managers in functional areas such as sales, purchasing, production, and cash disbursements to oversee and control their operations. By summarizing activities, highlighting trends, and identifying exceptions from normal performance, well-designed management reports provide evidence of internal control function or malfunction. In Chapter 8, we review the management reporting system and examine the characteristics of effective management reports.

Control Activities

Control activities are the policies and procedures used to ensure that appropriate actions are taken to deal with the organization’s identified risks. Control activities can be grouped into two distinct categories: in- formation technology (IT) controls and physical controls.

IT CONTROLS. IT controls relate specifically to the computer environment. They fall into two broad groups: general controls and application controls. General controls pertain to entity-wide concerns such as controls over the data center, organization databases, systems development, and program maintenance. Application controls ensure the integrity of specific systems such as sales order processing, accounts payable, and payroll applications. Chapters 15, 16, and 17 are devoted to this extensive body of material. In the several chapters that follow, however, we shall see how physical control concepts apply in specific systems.

PHYSICAL CONTROLS. This class of controls relates primarily to the human activities employed in accounting systems. These activities may be purely manual, such as the physical custody of assets, or they may involve the physical use of computers to record transactions or update accounts. Physical controls do not relate to the computer logic that actually performs accounting tasks. Rather, they relate to the human activities that trigger and utilize the results of those tasks. In other words, physical controls focus on people, but are not restricted to an environment in which clerks update paper accounts with pen and ink. Virtually all systems, regardless of their sophistication, employ human activities that need to be controlled.

Our discussion will address the issues pertaining to six categories of physical control activities: trans- action authorization, segregation of duties, supervision, accounting records, access control, and independent verification.

TRANSACTION AUTHORIZATION. The purpose of transaction authorization is to ensure that all material transactions processed by the information system are valid and in accordance with management’s objectives. Authorizations may be general or specific. General authority is granted to operations personnel to perform day-to-day operations. An example of general authorization is the procedure to authorize the purchase of inventories from a designated vendor only when inventory levels fall to their predetermined reorder points. This is called a programmed procedure (not necessarily in the computer sense of the word) in which the decision rules are specified in advance, and no additional approvals are required. On the other hand, specific authorizations deal with case-by-case decisions associated with nonroutine transactions. An example of this is the decision to extend a particular customer’s credit limit beyond the normal amount. Specific authority is usually a management responsibility.

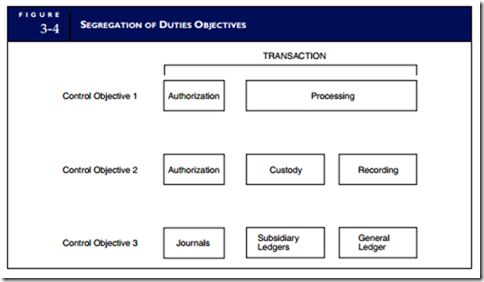

SEGREGATION OF DUTIES. One of the most important control activities is the segregation of employee duties to minimize incompatible functions. Segregation of duties can take many forms, depending on the specific duties to be controlled. However, the following three objectives provide general guidelines applicable to most organizations. These objectives are illustrated in Figure 3-4.

Objective 1. The segregation of duties should be such that the authorization for a transaction is separate from the processing of the transaction. For example, the purchasing department should not initiate purchases until the inventory control department gives authorization. This separation of tasks is a control to prevent individuals from purchasing unnecessary inventory.

Objective 2. Responsibility for the custody of assets should be separate from the record-keeping responsibility. For example, the department that has physical custody of finished goods inventory (the warehouse) should not keep the official inventory records. Accounting for finished goods inventory is performed by inventory control, an accounting function. When a single individual or department has responsibility for both asset custody and record keeping, the potential for fraud exists. Assets can be stolen or lost and the accounting records falsified to hide the event.

Objective 3. The organization should be structured so that a successful fraud requires collusion between two or more individuals with incompatible responsibilities. For example, no individual should have sufficient access to accounting records to perpetrate a fraud. Thus, journals, subsidiary ledgers, and the general ledger are maintained separately. For most people, the thought of approaching another employee with the proposal to collude in a fraud presents an insurmountable psychological barrier. The fear of rejection and subsequent disciplinary action discourages solicitations of this sort. However, when employees with incompatible responsibilities work together daily in close quarters, the resulting familiarity tends to erode this barrier. For this reason, the segregation of incompatible tasks should be physical as well as organizational. Indeed, concern about personal familiarity on the job is the justification for establishing rules prohibiting nepotism.

SUPERVISION. Implementing adequate segregation of duties requires that a firm employ a sufficiently large number of employees. Achieving adequate segregation of duties often presents difficulties for small organizations. Obviously, it is impossible to separate five incompatible tasks among three employees. Therefore, in small organizations or in functional areas that lack sufficient personnel, management must compensate for the absence of segregation controls with close supervision. For this reason, supervision is often called a compensating control.

An underlying assumption of supervision control is that the firm employs competent and trustworthy personnel. Obviously, no company could function for long on the alternative assumption that its employees are incompetent and dishonest. The competent and trustworthy employee assumption promotes supervisory efficiency. Firms can thus establish a managerial span of control whereby a single manager supervises several employees. In manual systems, maintaining a span of control tends to be straightfor- ward because both manager and employees are at the same physical location.

ACCOUNTING RECORDS. The accounting records of an organization consist of source documents, journals, and ledgers. These records capture the economic essence of transactions and provide an audit trail of economic events. The audit trail enables the auditor to trace any transaction through all phases of its processing from the initiation of the event to the financial statements. Organizations must maintain audit trails for two reasons. First, this information is needed for conducting day-to-day operations. The audit trail helps employees respond to customer inquiries by showing the current status of transactions in process. Second, the audit trail plays an essential role in the financial audit of the firm. It enables external (and internal) auditors to verify selected transactions by tracing them from the financial statements to the ledger accounts, to the journals, to the source documents, and back to their original source. For reasons of both practical expedience and legal obligation, business organizations must maintain sufficient accounting records to preserve their audit trails.

ACCESS CONTROL. The purpose of access controls is to ensure that only authorized personnel have access to the firm’s assets. Unauthorized access exposes assets to misappropriation, damage, and theft. Therefore, access controls play an important role in safeguarding assets. Access to assets can be direct or indirect. Physical security devices, such as locks, safes, fences, and electronic and infrared alarm systems, control against direct access. Indirect access to assets is achieved by gaining access to the records and documents that control the use, ownership, and disposition of the asset. For example, an individual with access to all the relevant accounting records can destroy the audit trail that describes a particular sales transaction. Thus, by removing the records of the transaction, including the accounts receivable balance, the sale may never be billed and the firm will never receive payment for the items sold. The access controls needed to protect accounting records will depend on the technological characteristics of the accounting system. Indirect access control is accomplished by controlling the use of documents and records and by segregating the duties of those who must access and process these records.

INDEPENDENT VERIFICATION. Verification procedures are independent checks of the account- ing system to identify errors and misrepresentations. Verification differs from supervision because it takes place after the fact, by an individual who is not directly involved with the transaction or task being verified. Supervision takes place while the activity is being performed, by a supervisor with direct responsibility for the task. Through independent verification procedures, management can assess (1) the performance of individuals, (2) the integrity of the transaction processing system, and (3) the correctness of data contained in accounting records. Examples of independent verifications include:

• Reconciling batch totals at points during transaction processing.

• Comparing physical assets with accounting records.

• Reconciling subsidiary accounts with control accounts.

• Reviewing management reports (both computer and manually generated) that summarize business activity.

The timing of verification depends on the technology employed in the accounting system and the task under review. Verifications may occur several times an hour or several times a day. In some cases, a veri- fication may occur daily, weekly, monthly, or annually.

Comments

Post a Comment