Ethics, Fraud, and Internal Control:Fraud and Accountants

Fraud and Accountants

Perhaps no major aspect of the independent auditor’s role has caused more controversy than their responsibility for detecting fraud during an audit. In recent years, the structure of the U.S. financial reporting system has become the object of scrutiny. The SEC, the courts, and the public, along with Congress, have focused on business failures and questionable practices by the management of corporations that engage in alleged fraud. The question often asked is, ‘‘Where were the auditors?’’

The passage of SOX has had a tremendous impact on the external auditor’s responsibilities for fraud detection during a financial audit. It requires the auditor to test controls specifically intended to prevent or detect fraud likely to result in a material misstatement of the financial statements. The current authoritative guidelines on fraud detection are presented in Statement on Auditing Standards (SAS) No. 99, Consideration of Fraud in a Financial Statement Audit. The objective of SAS 99 is to seamlessly blend the auditor’s consideration of fraud into all phases of the audit process. In addition, SAS 99 requires the auditor to perform new steps such as a brainstorming during audit planning to assess the potential risk of material misstatement of the financial statements from fraud schemes.

DEFINITIONS OF FRAUD

Although fraud is a familiar term in today’s financial press, its meaning is not always clear. For example, in cases of bankruptcies and business failures, alleged fraud is often the result of poor management decisions or adverse business conditions. Under such circumstances, it becomes necessary to clearly define and understand the nature and meaning of fraud.

Fraud denotes a false representation of a material fact made by one party to another party with the intent to deceive and induce the other party to justifiably rely on the fact to his or her detriment. According to common law, a fraudulent act must meet the following five conditions:

1. False representation. There must be a false statement or a nondisclosure.

2. Material fact. A fact must be a substantial factor in inducing someone to act.

3. Intent. There must be the intent to deceive or the knowledge that one’s statement is false.

4. Justifiable reliance. The misrepresentation must have been a substantial factor on which the injured party relied.

5. Injury or loss. The deception must have caused injury or loss to the victim of the fraud.

Fraud in the business environment has a more specialized meaning. It is an intentional deception, misappropriation of a company’s assets, or manipulation of its financial data to the advantage of the perpetrator. In accounting literature, fraud is also commonly known as white-collar crime, defalcation, embezzlement, and irregularities. Auditors encounter fraud at two levels: employee fraud and management fraud. Because each form of fraud has different implications for auditors, we need to distinguish between the two.

Employee fraud, or fraud by nonmanagement employees, is generally designed to directly convert cash or other assets to the employee’s personal benefit. Typically, the employee circumvents the com- pany’s internal control system for personal gain. If a company has an effective system of internal control, defalcations or embezzlements can usually be prevented or detected.

Employee fraud usually involves three steps: (1) stealing something of value (an asset), (2) converting the asset to a usable form (cash), and (3) concealing the crime to avoid detection. The third step is often the most difficult. It may be relatively easy for a storeroom clerk to steal inventories from the employer’s warehouse, but altering the inventory records to hide the theft is more of a challenge.

Management fraud is more insidious than employee fraud because it often escapes detection until the organization has suffered irreparable damage or loss. Management fraud usually does not involve the direct theft of assets. Top management may engage in fraudulent activities to drive up the market price of the company’s stock. This may be done to meet investor expectations or to take advantage of stock options that have been loaded into the manager’s compensation package. The Commission on Auditors’ Responsibilities calls this performance fraud, which often involves deceptive practices to inflate earnings or to forestall the recognition of either insolvency or a decline in earnings. Lower-level management fraud typically involves materially misstating financial data and internal reports to gain additional compensation, to garner a promotion, or to escape the penalty for poor performance. Management fraud typically contains three special characteristics:10

1. The fraud is perpetrated at levels of management above the one to which internal control structures generally relate.

2. The fraud frequently involves using the financial statements to create an illusion that an entity is healthier and more prosperous than, in fact, it is.

3. If the fraud involves misappropriation of assets, it frequently is shrouded in a maze of complex busi- ness transactions, often involving related third parties.

The preceding characteristics of management fraud suggest that management can often perpetrate irregularities by overriding an otherwise effective internal control structure that would prevent similar irregularities by lower-level employees.

THE FRAUD TRIANGLE

The fraud triangle consists of three factors that contribute to or are associated with management and employee fraud. These are (1) situational pressure, which includes personal or job-related stresses that could coerce an individual to act dishonestly; (2) opportunity, which involves direct access to assets and/or access to information that controls assets, and; (3) ethics, which pertains to one’s character and degree of moral opposition to acts of dishonesty. Figure 3-1 graphically depicts the interplay among these three forces. The figure suggests that an individual with a high level of personal ethics, who is confronted by low pressure and limited opportunity to commit fraud, is more likely to behave honestly than one with weaker personal ethics, who is under high pressure and exposed to greater fraud opportunities.

Research by forensic experts and academics has shown that the auditor’s evaluation of fraud is enhanced when the fraud triangle factors are considered. Obviously, matters of ethics and personal stress do not lend themselves to easy observation and analysis. To provide insight into these factors, auditors of- ten use a red-flag checklist consisting of the following types of questions:11

• Do key executives have unusually high personal debt?

• Do key executives appear to be living beyond their means?

• Do key executives engage in habitual gambling?

• Do key executives appear to abuse alcohol or drugs?

• Do any of the key executives appear to lack personal codes of ethics?

• Are economic conditions unfavorable within the company’s industry?

• Does the company use several different banks, none of which sees the company’s entire financial picture?

• Do any key executives have close associations with suppliers?

• Is the company experiencing a rapid turnover of key employees, either through resignation or termination?

• Do one or two individuals dominate the company?

A review of some of these questions shows that contemporary auditors may need to use professional investigative agencies to run confidential background checks on key managers of existing and prospective client firms.

FINANCIAL LOSSES FROM FRAUD

A research study published by the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE) in 2008 estimates losses from fraud and abuse to be 7 percent of annual revenues. This translates to approximately $994 bil- lion in fraud losses for 2008. The actual cost of fraud is, however, difficult to quantify for a number of reasons: (1) not all fraud is detected; (2) of that detected, not all is reported; (3) in many fraud cases, incomplete information is gathered; (4) information is not properly distributed to management or law enforcement authorities; and (5) too often, business organizations decide to take no civil or criminal action against the perpetrator(s) of fraud. In addition to the direct economic loss to the organization, indirect costs including reduced productivity, the cost of legal action, increased unemployment, and business disruption due to investigation of the fraud need to be considered.

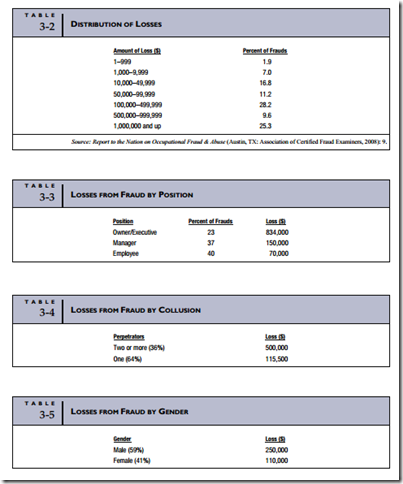

Of the 959 occupational fraud cases examined in the ACFE study, the median loss from fraud was $175,000, while 25 percent of the organizations experienced losses of $1 million or more. The distribution of dollar losses is presented in Table 3-2.

THE PERPETRATORS OF FRAUDS

The ACFE study examined a number of factors that profile the perpetrators of the frauds, including position within the organization, collusion with others, gender, age, and education. The median financial loss was calculated for each factor. The results of the study are summarized in Tables 3-3 through 3-7.12

Fraud Losses by Position within the Organization

Table 3-3 shows that 40 percent of the reported fraud cases were committed by nonmanagerial employees, 37 percent by managers, and 23 percent by executives or owners. Although the reported number of frauds perpetrated by employees is higher than that of managers and almost twice that of executives, the average losses per category are inversely related.

Fraud Losses and the Collusion Effect

Collusion among employees in the commission of a fraud is difficult to both prevent and detect. This is particularly true when the collusion is between managers and their subordinate employees. Management plays a key role in the internal control structure of an organization. They are relied upon to prevent and detect fraud among their subordinates. When they participate in fraud with the employees over whom they are supposed to provide oversight, the organization’s control structure is weakened, or completely circumvented, and the company becomes more vulnerable to losses.

Table 3-4 compares the median losses from frauds committed by individuals acting alone (regardless of position) and frauds involving collusion. This includes both internal collusion and schemes in which an employee or manager colludes with an outsider such as a vendor or a customer. Although frauds involving collusion are less common (36 percent of cases), the median loss is $500,000 as compared to $115,500 for frauds perpetrated by individuals working alone.

Fraud Losses by Gender

Table 3-5 shows that the median fraud loss per case caused by males ($250,000) was more than twice that caused by females ($110,000).

Fraud Losses by Age

Table 3-6 indicates that perpetrators younger than 26 years of age caused median losses of $25,000, while those perpetrated by individuals 60 and older were approximately 20 times larger.

Fraud Losses by Education

Table 3-7 shows the median loss from frauds relative to the perpetrator’s education level. Frauds commit- ted by high school graduates averaged only $100,000, whereas those with bachelor’s degrees averaged $210,000. Perpetrators with advanced degrees were responsible for frauds with a median loss of $550,000.

Conclusions to Be Drawn

Although the ACFE fraud study results are interesting, they appear to provide little in the way of anti- fraud decision-making criteria. Upon closer examination, however, a common thread appears. Notwith- standing the importance of personal ethics and situational pressures in inducing one to commit fraud, opportunity is the factor that actually facilitates the act. Opportunity was defined previously as access to assets and/or the information that controls assets. No matter how intensely driven by situational pressure one may become, even the most unethical individual cannot perpetrate a fraud if no opportunity to do so exists. Indeed, the opportunity factor explains much of the financial loss differential in each of the demo- graphic categories presented in the ACFE study:

• Position. Individuals in the highest positions within an organization are beyond the internal control structure and have the greatest access to company funds and assets.

• Gender. Women are not fundamentally more honest than men, but men occupy high corporate positions in greater numbers than women. This affords men greater access to assets.

• Age. Older employees tend to occupy higher-ranking positions and therefore generally have greater access to company assets.

• Education. Generally, those with more education occupy higher positions in their organizations and therefore have greater access to company funds and other assets.

• Collusion. One reason for segregating occupational duties is to deny potential perpetrators the opportunity they need to commit fraud. When individuals in critical positions collude, they create opportunities to control or gain access to assets that otherwise would not exist.

FRAUD SCHEMES

Fraud schemes can be classified in a number of different ways. For purposes of discussion, this section presents the ACFE classification format. Three broad categories of fraud schemes are defined: fraudulent statements, corruption, and asset misappropriation.13

Fraudulent Statements

Fraudulent statements are associated with management fraud. Whereas all fraud involves some form of fi- nancial misstatement, to meet the definition under this class of fraud scheme the statement itself must bring direct or indirect financial benefit to the perpetrator. In other words, the statement is not simply a vehicle for obscuring or covering a fraudulent act. For example, misstating the cash account balance to cover the theft of cash is not financial statement fraud. On the other hand, understating liabilities to present a more favorable financial picture of the organization to drive up stock prices does fall under this classification.

Table 3-8 shows that whereas fraudulent statements account for only 10 percent of the fraud cases covered in the ACFE fraud study, the median loss from this type of fraud scheme is significantly higher than losses from corruption and asset misappropriation.

Appalling as this type of fraud loss appears on paper, these numbers fail to reflect the human suffering that parallels them in the real world. How does one measure the impact on stockholders as they watch their life savings and retirement funds evaporate after news of the fraud breaks? The underlying problems that permit and aid these frauds are found in the boardroom, not the mail room. In this section, we examine some prominent corporate governance failures and the legislation to remedy them.

THE UNDERLYING PROBLEMS. The series of events symbolized by the Enron, WorldCom, and Adelphia debacles caused many to question whether our existing federal securities laws were adequate to ensure full and fair financial disclosures by public companies. The following underlying problems are at the root of this concern.

1. Lack of Auditor Independence. Auditing firms that are also engaged by their clients to perform non- accounting activities such as actuarial services, internal audit outsourcing services, and consulting, lack independence. The firms are essentially auditing their own work. The risk is that as auditors they will not bring to management’s attention detected problems that may adversely affect their consulting fees. For example, Enron’s auditors—Arthur Andersen—were also their internal auditors and their management consultants.

2. Lack of Director Independence. Many boards of directors are composed of individuals who are not in- dependent. Examples of lack of independence are directors who have a personal relationship by serving on the boards of other directors’ companies; have a business trading relationship as key customers or suppliers of the company; have a financial relationship as primary stockholders or have received personal loans from the company; or have an operational relationship as employees of the company.

A notorious example of corporate inbreeding is Adelphia Communications, a telecommunications company. Founded in 1952, it went public in 1986 and grew rapidly through a series of acquisitions. It became the sixth largest cable provider in the United States before an accounting scandal came to light. The founding family (John Rigas, CEO and chairman of the board; Timothy Rigas, CFO, Chief Administrative Officer, and chairman of the audit committee; Michael Rigas, Vice President for operation; and J.P. Rigas, Vice President for strategic planning) perpetrated the fraud. Between 1998 and May 2002, the Rigas family successfully disguised transactions, distorted the company’s financial picture, and engaged in embezzlement that resulted in a loss of more than $60 billion to shareholders.

Whereas it is neither practical nor wise to establish a board of directors that is totally void of self- interest, popular wisdom suggests that a healthier board of directors is one in which the majority of directors are independent outsiders, with the integrity and the qualifications to understand the company and objectively plan its course.

3. Questionable Executive Compensation Schemes. A Thomson Financial survey revealed the strong belief that executives have abused stock-based compensation.14 The consensus is that fewer stock options should be offered than currently is the practice. Excessive use of short-term stock options to compensate directors and executives may result in short-term thinking and strategies aimed at driving up stock prices at the expense of the firm’s long-term health. In extreme cases, financial statement misrepresentation has been the vehicle to achieve the stock price needed to exercise the option.

As a case in point, Enron’s management was a firm believer in the use of stock options. Nearly every employee had some type of arrangement by which he or she could purchase shares at a discount or were granted options based on future share prices. At Enron’s headquarters in Houston, televisions were installed in the elevators so employees could track Enron’s (and their own portfolio’s) success. Before the firm’s collapse, Enron executives added millions of dollars to their personal fortunes by exercising stock options.

4. Inappropriate Accounting Practices. The use of inappropriate accounting techniques is a characteristic common to many financial statement fraud schemes. Enron made elaborate use of special-purpose entities to hide liabilities through off-balance-sheet accounting. Special-purpose entities are legal, but their application in this case was clearly intended to deceive the market. Enron also employed income-inflating techniques. For example, when the company sold a contract to provide natural gas for a period of two years, they would recognize all the future revenue in the period when the contract was sold.

WorldCom was another culprit of the improper accounting practices. In April 2001, WorldCom management decided to transfer transmission line costs from current expense accounts to capital accounts. This allowed them to defer some operating expenses and report higher earnings. Also, through acquisitions, they seized the opportunity to raise earnings. WorldCom reduced the book value of hard assets of MCI by $3.4 billion and increased goodwill by the same amount. Had the assets been left at book value, they would have been charged against earnings over four years. Good- will, on the other hand, was amortized over a much longer period. In June 2002, the company declared a $3.8 billion overstatement of profits because of falsely recorded expenses over the previ- ous five quarters. The size of this fraud increased to $9 billion over the following months as additional evidence of improper accounting came to light.

SARBANES-OXLEY ACT AND FRAUD. To address plummeting institutional and individual investor confidence triggered in part by business failures and accounting restatements, Congress enacted SOX into law in July 2002. This landmark legislation was written to deal with problems related to capital markets, corporate governance, and the auditing profession and has fundamentally changed the way public companies do business and how the accounting profession performs its attest function. Some SOX rules became effective almost immediately, and others were phased in over time. In the short time since it was enacted, however, SOX is now largely implemented.

The act establishes a framework to modernize and reform the oversight and regulation of public company auditing. Its principal reforms pertain to (1) the creation of an accounting oversight board, (2) auditor independence, (3) corporate governance and responsibility, (4) disclosure requirements, and (5) penalties for fraud and other violations. These provisions are discussed in the following section.

1. Accounting Oversight Board. SOX created a Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB). The PCAOB is empowered to set auditing, quality control, and ethics standards; to inspect registered accounting firms; to conduct investigations; and to take disciplinary actions.

2. Auditor Independence. The act addresses auditor independence by creating more separation between a firm’s attestation and nonauditing activities. This is intended to specify categories of services that a public accounting firm cannot perform for its client. These include the following nine functions:

a. Bookkeeping or other services related to the accounting records or financial statements

b. Financial information systems design and implementation

c. Appraisal or valuation services, fairness opinions, or contribution-in-kind reports

d. Actuarial services

e. Internal audit outsourcing services

f. Management functions or human resources

g. Broker or dealer, investment adviser, or investment banking services

h. Legal services and expert services unrelated to the audit

i. Any other service that the PCAOB determines is impermissible

Whereas SOX prohibits auditors from providing these services to their audit clients, they are not pro- hibited from performing such services for nonaudit clients or privately held companies.

3. Corporate Governance and Responsibility. The act requires all audit committee members to be inde- pendent and requires the audit committee to hire and oversee the external auditors. This provision is consistent with many investors who consider the board composition to be a critical investment factor. For example, a Thomson Financial survey revealed that most institutional investors want corporate boards to be composed of at least 75 percent independent directors.15

Two other significant provisions of the act relating to corporate governance are (1) public companies are prohibited from making loans to executive officers and directors, and (2) the act requires attorneys to report evidence of a material violation of securities laws or breaches of fiduciary duty to the CEO, CFO, or the PCAOB.

4. Issuer and Management Disclosure. SOX imposes new corporate disclosure requirements, including:

a. Public companies must report all off-balance-sheet transactions.

b. Annual reports filed with the SEC must include a statement by management asserting that it is responsible for creating and maintaining adequate internal controls and asserting to the effectiveness of those controls.

c. Officers must certify that the company’s accounts ‘‘fairly present’’ the firm’s financial condition and results of operations.

d. Knowingly filing a false certification is a criminal offense.

5. Fraud and Criminal Penalties. SOX imposes a range of new criminal penalties for fraud and other wrongful acts. In particular, the act creates new federal crimes relating to the destruction of documents or audit work papers, securities fraud, tampering with documents to be used in an official pro- ceeding, and actions against whistle-blowers.

Corruption

Corruption involves an executive, manager, or employee of the organization in collusion with an out- sider. The ACFE study identifies four principal types of corruption: bribery, illegal gratuities, conflicts of interest, and economic extortion. Corruption accounts for about 10 percent of occupational fraud cases.

BRIBERY. Bribery involves giving, offering, soliciting, or receiving things of value to influence an of- ficial in the performance of his or her lawful duties. Officials may be employed by government (or regulatory) agencies or by private organizations. Bribery defrauds the entity (business organization or government agency) of the right to honest and loyal services from those employed by it. For example, the manager of a meat-packing company offers a U.S. health inspector a cash payment. In return, the inspector suppresses his report of health violations discovered during a routine inspection of the meat-packing facilities. In this situation, the victims are those who rely on the inspector’s honest reporting. The loss is salary paid to the inspector for work not performed and any damages that result from failure to perform.

ILLEGAL GRATUITIES. An illegal gratuity involves giving, receiving, offering, or soliciting some- thing of value because of an official act that has been taken. This is similar to a bribe, but the transaction occurs after the fact. For example, the plant manager in a large corporation uses his influence to ensure that a request for proposals is written in such a way that only one contractor will be able to submit a satisfactory bid. As a result, the favored contractor’s proposal is accepted at a noncompetitive price. In return, the contractor secretly makes a financial payment to the plant manager. The victims in this case are those who expect a competitive procurement process. The loss is the excess costs the company incurs because of the noncompetitive pricing of the construction.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST. Every employer should expect that his or her employees will conduct their duties in a way that serves the interests of the employer. A conflict of interest occurs when an employee acts on behalf of a third party during the discharge of his or her duties or has self-interest in the activity being performed. When the employee’s conflict of interest is unknown to the employer and results in financial loss, then fraud has occurred. The preceding examples of bribery and illegal gratuities also constitute conflicts of interest. This type of fraud can exist, however, when bribery and illegal payments are not present, but the employee has an interest in the outcome of the economic event. For example, a purchasing agent for a building contractor is also part owner in a plumbing supply company. The agent has sole discretion in selecting vendors for the plumbing supplies needed for buildings under contract. The agent directs a disproportionate number of purchase orders to his company, which charges above- market prices for its products. The agent’s financial interest in the supplier is unknown to his employer.

ECONOMIC EXTORTION. Economic extortion is the use (or threat) of force (including economic sanctions) by an individual or organization to obtain something of value. The item of value could be a fi- nancial or economic asset, information, or cooperation to obtain a favorable decision on some matter under review. For example, a contract procurement agent for a state government threatens to blacklist a highway contractor if he does not make a financial payment to the agent. If the contractor fails to cooper- ate, the blacklisting will effectively eliminate him from consideration for future work. Faced with a threat of economic loss, the contractor makes the payment.

Asset Misappropriation

The most common fraud schemes involve some form of asset misappropriation in which assets are either directly or indirectly diverted to the perpetrator’s benefit. Ninety percent of the frauds included in the ACFE study fall in this general category. Certain assets are, however, more susceptible than others to misappropriation. Transactions involving cash, checking accounts, inventory, supplies, equipment, and information are the most vulnerable to abuse. Table 3-9 shows the percent of occurrence and the medium value of fraud losses in eight subcategories of asset misappropriation. The following sections provide definitions and examples of the fraud schemes listed in the table.

Skimming

Skimming involves stealing cash from an organization before it is recorded on the organization’s books and records. One example of skimming is an employee who accepts payment from a customer but does not record the sale. Another example is mail room fraud in which an employee opening the mail steals a customer’s check and destroys the associated remittance advice. By destroying the remittance advice, no evidence of the cash receipt exists. This type of fraud may continue for several weeks or months until detected. Ultimately the fraud will be detected when the customer complains that his account has not been credited. By that time, however, the mail room employee will have left the organization and moved on.

Cash Larceny

Cash larceny involves schemes in which cash receipts are stolen from an organization after they have been recorded in the organization’s books and records. An example of this is lapping, in which the cash receipts clerk first steals and cashes a check from Customer A. To conceal the accounting imbalance caused by the loss of the asset, Customer A’s account is not credited. Later (the next billing period), the employee uses a check received from Customer B and applies it to Customer A’s account. Funds received in the next period from Customer C are then applied to the account of Customer B, and so on.

Employees involved in this sort of fraud often rationalize that they are simply borrowing the cash and plan to repay it at some future date. This kind of accounting cover-up must continue indefinitely or until the employee returns the funds. Lapping is usually detected when the employee leaves the organization or becomes sick and must take time off from work. Unless the fraud is perpetuated, the last customer to have funds diverted from his or her account will be billed again, and the lapping technique will be detected. Employers can deter lapping by periodically rotating employees into different jobs and forcing them to take scheduled vacations.

Billing Schemes

Billing schemes, also known as vendor fraud, are perpetrated by employees who causes their employer to issue a payment to a false supplier or vendor by submitting invoices for fictitious goods or services, inflated invoices, or invoices for personal purchases. Three examples of billing scheme are presented here.

A shell company fraud first requires that the perpetrator establish a false supplier on the books of the victim company. The fraudster then manufactures false purchase orders, receiving reports, and invoices in the name of the vendor and submits them to the accounting system, which creates the allusion of a legiti- mate transaction. Based on these documents, the system will set up an account payable and ultimately issue a check to the false supplier (the fraudster). This sort of fraud may continue for years before it is detected.

A pass through fraud is similar to the shell company fraud with the exception that a transaction actually takes place. Again, the perpetrator creates a false vendor and issues purchase orders to it for inventory or supplies. The false vendor then purchases the needed inventory from a legitimate vendor. The false vendor charges the victim company a much higher than market price for the items, but pays only the market price to the legitimate vendor. The difference is the profit that the perpetrator pockets.

A pay-and-return scheme is a third form of vendor fraud. This typically involves a clerk with check- writing authority who pays a vendor twice for the same products (inventory or supplies) received. The vendor, recognizing that its customer made a double payment, issues a reimbursement to the victim company, which the clerk intercepts and cashes.

Check Tampering

Check tampering involves forging or changing in some material way a check that the organization has written to a legitimate payee. One example of this is an employee who steals an outgoing check to a vendor, forges the payee’s signature, and cashes the check. A variation on this is an employee who steals blank checks from the victim company makes them out to himself or an accomplice.

Payroll Fraud

Payroll fraud is the distribution of fraudulent paychecks to existent and/or nonexistent employees. For example, a supervisor keeps an employee on the payroll who has left the organization. Each week, the supervisor continues to submit time cards to the payroll department as if the employee were still working for the victim organization. The fraud works best in organizations in which the supervisor is responsible for distributing paychecks to employees. The supervisor may intercept the paycheck, forge the former employee’s signature, and cash it. Another example of payroll fraud is to inflate the hours worked on an employee time card so that he or she will receive a larger than deserved paycheck. This type of fraud of- ten involves collusion with the supervisor or timekeeper.

Expense Reimbursements

Expense reimbursement frauds are schemes in which an employee makes a claim for reimbursement of fictitious or inflated business expenses. For example, a company salesperson files false expense reports, claiming meals, lodging, and travel that never occurred.

Thefts of Cash

Thefts of cash are schemes that involve the direct theft of cash on hand in the organization. An example of this is an employee who makes false entries on a cash register, such as voiding a sale, to conceal the fraudulent removal of cash. Another example is a bank employee who steals cash from the vault.

Non-Cash Misappropriations

Non-cash fraud schemes involve the theft or misuse of the victim organization’s non-cash assets. One example of this is a warehouse clerk who steals inventory from a warehouse or storeroom. Another example is a customer services clerk who sells confidential customer information to a third party.

Computer Fraud

Because computers lie at the heart of modern accounting information systems, the topic of computer fraud is of importance to auditors. Although the fundamental structure of fraud is unchanged by computers—fraudulent statements, corruption, and asset misappropriation—computers do add complexity to the fraud picture. To fully appreciate these complexities requires an awareness of technology and internal control issues that are discussed in subsequent chapters. Computer fraud is therefore deferred to Chapter 15, wherein we examine a number of related topics.

Comments

Post a Comment