The Information System:Organizational Structure

Organizational Structure

The structure of an organization reflects the distribution of responsibility, authority, and accountability throughout the organization. These flows are illustrated in Figure 1-7. Firms achieve their overall objectives by establishing measurable financial goals for their operational units. For example, budget information flows downward. This is the mechanism by which senior management conveys to their subordinates the standards against which they will be measured for the coming period. The results of the subordinates’ actions, in the form of performance information, flow upward to senior management. Understanding the distribution pat- tern of responsibility, authority, and accountability is essential for assessing user information needs.

BUSINESS SEGMENTS

Business organizations consist of functional units or segments. Firms organize into segments to promote internal efficiencies through the specialization of labor and cost-effective resource allocations. Managers within a segment can focus their attention on narrow areas of responsibility to achieve higher levels of operating efficiency. Three of the most common approaches include segmentation by:

1. Geographic Location. Many organizations have operations dispersed across the country and around the world. They do this to gain access to resources, markets, or lines of distribution. A convenient way to manage such operations is to organize the management of the firm around each geographic segment as a quasi-autonomous entity.

2. Product Line. Companies that produce highly diversified products often organize around product lines, creating separate divisions for each. Product segmentation allows the organization to devote specialized management, labor, and resources to segments separately, almost as if they were separate firms.

3. Business Function. Functional segmentation divides the organization into areas of specialized responsibility based on tasks. The functional areas are determined according to the flow of primary resources through the firm. Examples of business function segments are marketing, production, finance, and accounting.

Some firms use more than one method of segmentation. For instance, an international conglomerate may segment its operations first geographically, then by product within each geographic region, and then functionally within each product segment.

FUNCTIONAL SEGMENTATION

Segmentation by business function is the most common method of organizing. To illustrate it, we will assume a manufacturing firm that uses these resources: materials, labor, financial capital, and information. Table 1-2 shows the relationship between functional segments and these resources.

The titles of functions and even the functions themselves will vary greatly among organizations, depending on their size and line of business. A public utility may have little in the way of a marketing function compared with an automobile manufacturer. A service organization may have no formal production function and little in the way of inventory to manage. One firm may call its labor resource personnel, whereas another uses the term human resources. Keeping in mind these variations, we will briefly discuss the functional areas of the hypothetical firm shown in Figure 1-8. Because of their special importance to

the study of information systems, the accounting and information technology (IT) functions are given separate and more detailed treatment.

Materials Management

The objective of materials management is to plan and control the materials inventory of the company. A manufacturing firm must have sufficient inventories on hand to meet its production needs and yet avoid excessive inventory levels. Every dollar invested in inventory is a dollar that is not earning a return. Furthermore, idle inventory can become obsolete, lost, or stolen. Ideally, a firm would coordinate inventory arrivals from suppliers such that they move directly into the production process. As a practical matter, however, most organizations maintain safety stocks to carry them through the lead time between placing the order for inventory and its arrival. We see from Figure 1-8 that materials management has three sub- functions:

1. Purchasing is responsible for ordering inventory from vendors when inventory levels fall to their reorder points. The nature of this task varies among organizations. In some cases, purchasing is no more than sending a purchase order to a designated vendor. In other cases, this task involves solicit- ing bids from a number of competing vendors. The nature of the business and the type of inventory determine the extent of the purchasing function.

2. Receiving is the task of accepting the inventory previously ordered by purchasing. Receiving activities include counting and checking the physical condition of these items. This is an organization’s first, and perhaps only, opportunity to detect incomplete deliveries and damaged merchandise before they move into the production process.

3. Stores takes physical custody of the inventory received and releases these resources into the production process as needed.

Production

Production activities occur in the conversion cycle in which raw materials, labor, and plant assets are used to create finished products. The specific activities are determined by the nature of the products being manufactured. In general they fall into two broad classes: (1) primary manufacturing activities and

(2) production support activities. Primary manufacturing activities shape and assemble raw materials into finished products. Production support activities ensure that primary manufacturing activities operate efficiently and effectively. These include, but are not limited to, the following types of activities:

Production planning involves scheduling the flow of materials, labor, and machinery to efficiently meet production needs. This requires information about the status of sales orders, raw materials inventory, finished goods inventory, and machine and labor availability.

Quality control monitors the manufacturing process at various points to ensure that the finished products meet the firm’s quality standards. Effective quality control detects problems early to facilitate corrective action. Failure to do so may result in excessive waste of materials and labor.

Maintenance keeps the firm’s machinery and other manufacturing facilities in running order. The manufacturing process relies on its plant and equipment and cannot tolerate breakdowns during peak production periods. Therefore, the key to maintenance is prevention—the scheduled removal of equipment from operations for cleaning, servicing, and repairs. Many manufacturers

have elaborate preventive maintenance programs. To plan and coordinate these activities, maintenance engineers need extensive information about the history of equipment usage and future scheduled production.

Marketing

The marketplace needs to know about, and have access to, a firm’s products. The marketing function deals with the strategic problems of product promotion, advertising, and market research. On an operational level, marketing performs such daily activities as sales order entry.

Distribution is the activity of getting the product to the customer after the sale. This is a critical step. Much can go wrong before the customer takes possession of the product. Excessive lags between the taking and filling of orders, incorrect shipments, or damaged merchandise can result in customer dissatisfaction and lost sales. Ultimately, success depends on filling orders accurately in the warehouse, packaging goods correctly, and shipping them quickly to the customer.

Personnel

Competent and reliable employees are a valuable resource to a business. The objective of the personnel function is to effectively manage this resource. A well-developed personnel function includes recruiting, training, continuing education, counseling, evaluating, labor relations, and compensation administration.

Finance

The finance function manages the financial resources of the firm through banking and treasury activities, portfolio management, credit evaluation, cash disbursements, and cash receipts. Because of the cyclical nature of business, many firms swing between positions of excess funds and cash deficits. In response to these cash flow patterns, financial planners seek lucrative investments in stocks and other assets and low-cost lines of credit from banks. The finance function also administers the daily flow of cash in and out of the firm.

THE ACCOUNTING FUNCTION

The accounting function manages the financial information resource of the firm. In this regard, it plays two important roles in transaction processing. First, accounting captures and records the financial effects of the firm’s transactions. These include events such as the movement of raw materials from the ware- house into production, shipments of the finished products to customers, cash flows into the firm and deposits in the bank, the acquisition of inventory, and the discharge of financial obligations.

Second, the accounting function distributes transaction information to operations personnel to coordinate many of their key tasks. Accounting activities that contribute directly to business operations include inventory control, cost accounting, payroll, accounts payable, accounts receivable, billing, fixed asset accounting, and the general ledger. We deal with each of these specifically in later chapters. For the moment, however, we need to maintain a broad view of accounting to understand its functional role in the organization.

The Value of Information

The value of information to a user is determined by its reliability. We saw earlier that the purpose of in- formation is to lead the user to a desired action. For this to happen, information must possess certain attributes—relevance, accuracy, completeness, summarization, and timeliness. When these attributes are consistently present, information has reliability and provides value to the user. Unreliable information has no value. At best, it is a waste of resources; at worst, it can lead to dysfunctional decisions. Consider the following example:

A marketing manager signed a contract with a customer to supply a large quantity of product by a certain deadline. He made this decision based on information about finished goods inventory levels. However, because of faulty record keeping, the information was incorrect. The actual inventory levels of the product were insufficient to meet the order, and the necessary quantities could not be manufactured by the deadline. Failure to comply with the terms of the contract may result in litigation.

This poor sales decision was a result of flawed information. Effective decisions require information that has a high degree of reliability.

Accounting Independence

Information reliability rests heavily on the concept of accounting independence. Simply stated, account- ing activities must be separate and independent of the functional areas that maintain custody of physical resources. For example, accounting monitors and records the movement of raw materials into production and the sale of finished goods to customers. Accounting authorizes purchases of raw materials and the disbursement of cash payments to vendors and employees. Accounting supports these functions with in- formation but does not actively participate in the physical activities.

THE INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY FUNCTION

Returning to Figure 1-8, the final area to be discussed is the IT function. Like accounting, the IT function is associated with the information resource. Its activities can be organized in a number of different ways. One extreme structure is the centralized data processing approach; at the other extreme is the distributed data processing approach. Most organizational structures fall somewhere between these extremes and embody elements of both.

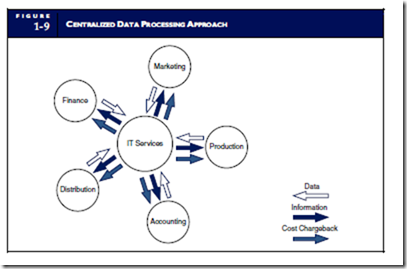

Centralized Data Processing

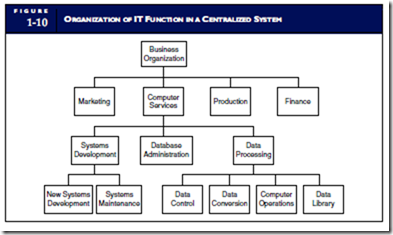

Under the centralized data processing model, all data processing is performed by one or more large computers housed at a central site that serve users throughout the organization. Figure 1-9 illustrates this approach in which IT activities are consolidated and managed as a shared organization resource. End users compete for these resources on the basis of need. The IT function is usually treated as a cost center whose operating costs are charged back to the end users. Figure 1-10 shows the IT areas of operation in more detail. These include database administration, data processing, and systems development and main- tenance. The key functions of each of these areas are described next.

DATA PROCESSING. The data processing group manages the computer resources used to perform the day-to-day processing of transactions. It may consist of the following functions: data control, data conversion, computer operations, and the data library.

Data control groups have all but disappeared from modern organizations. Traditionally, this function was responsible for receiving batches of transaction documents for processing from end users and then distributing computer output (documents and reports) back to the users. Today this function is usually automated and distributed back to the end users. Some organizations with older legacy systems, however, may still use a data control group as a liaison between the end user and data processing. The data conversion function transcribes transaction data from source (paper) documents to digital media (tape or disk) suitable for computer processing by the central computer, which is managed by the computer operations group. Accounting applications are usually run according to a strict schedule that is controlled by the central computer.

The data library is a room often adjacent to the computer center that provides safe storage for the off- line data files, such as magnetic tapes and removable disk packs. A data librarian who is responsible for the receipt, storage, retrieval, and custody of data files controls access to the library. The librarian issues tapes to computer operators and takes custody of files when processing is completed. The move to real- time processing and direct access files (discussed in Chapter 2) has reduced or eliminated the role of the data librarian in most organizations.

SYSTEMS DEVELOPMENT AND MAINTENANCE. The information needs of users are met by two related functions: systems development and systems maintenance. The former group is responsible for analyzing user needs and for designing new systems to satisfy those needs. The participants in system development include systems professionals, end users, and stakeholders.

Systems professionals include systems analysts, database designers, and programmers who design and build the system. Systems professionals gather facts about the user’s problem, analyze the facts, and formulate a solution. The product of their efforts is a new information system.

End users are those for whom the system is built. They are the managers who receive reports from the system and the operations personnel who work directly with the system as part of their daily responsibilities.

Stakeholders are individuals inside or outside the firm who have an interest in the system but are not end users. They include management, internal auditors, and consultants who oversee systems development.

Once a new system has been designed and implemented, the systems maintenance group assumes responsibility for keeping it current with user needs. Over the course of the system’s life (often several years), between 80 and 90 percent of its total cost will be attributable to maintenance activities.

Distributed Data Processing

An alternative to the centralized model is the concept of distributed data processing (DDP). The topic of DDP is quite broad, touching on such related topics as end-user computing, commercial software, net- working, and office automation. Simply stated, DDP involves reorganizing the IT function into small in- formation processing units (IPUs) that are distributed to end users and placed under their control. IPUs may be distributed according to business function, geographic location, or both. Any or all of the IT activities represented in Figure 1-10 may be distributed. Figure 1-11 shows a possible new organizational structure following the distribution of all data processing tasks to the end-user areas.

Notice that the central IT function has been eliminated from the organization structure. Individual operational areas now perform this role. In recent years, DDP has become an economic and operational feasibility that has revolutionized business operations. However, DDP is a mixed bag of advantages and disadvantages.

Mismanagement of organization-wide resources. Some argue that when organization-wide resources exceed a threshold amount, say 5 percent of the total operations budget, they should be con- trolled and monitored centrally. Information processing services (such as computer operations, programming, data conversion, and database management) represent a significant expenditure for many organizations. Those opposed to DDP argue that distributing responsibility for these resources will inevitably lead to their mismanagement and suboptimal utilization.

Hardware and software incompatibility. Distributing the responsibility for hardware and software purchases to user management can result in uncoordinated and poorly conceived decisions. Working independently, decision makers may settle on dissimilar and incompatible operating systems, technology plat- forms, spreadsheet programs, word processors, and database packages. Such hardware and software incompatibilities can degrade and disrupt communications between organizational units.

Redundant tasks. Autonomous systems development activities distributed throughout the firm can result in each user area reinventing the wheel. For example, application programs created by one user, which could be used with little or no change by others, will be redesigned from scratch rather than shared. Likewise, data common to many users may be recreated for each IPU, resulting in a high level of data redundancy.

Consolidating incompatible activities. The distribution of the IT function to individual user areas results in the creation of many very small units that may not permit the necessary separation of incom- patible functions. For example, within a single IPU, the same person may program applications, per- form program maintenance, enter transaction data into the computer, and operate the computer equipment. This situation represents a fundamental violation of internal control.

Hiring qualified professionals. End-user managers may lack the knowledge to evaluate the technical credentials and relevant experience of candidates applying for a position as a computer professional. Also, if the organizational unit into which a new employee is entering is small, the opportunity for personal growth, continuing education, and promotion may be limited. For these reasons, IPU managers sometimes experience difficulty attracting highly qualified personnel, which increases the risk of programming errors and systems failures.

Lack of standards. Because of the distribution of responsibility in the DDP environment, standards for developing and documenting systems, choosing programming languages, acquiring hardware and soft- ware, and evaluating performance may be unevenly applied or nonexistent. Opponents of DDP argue that the risks associated with the design and operation of a data processing system are made tolerable only if such standards are consistently applied. This requires that standards be imposed centrally.

ADVANTAGES OF DDP. The most commonly cited advantages of DDP are related to cost savings, increased user satisfaction, and improved operational efficiency. Specific issues are discussed in the following section.

Cost reductions. In the past, achieving economies of scale was the principal justification for the centralized approach. The economics of data processing favored large, expensive, powerful computers. The wide variety of needs that such centralized systems had to satisfy called for computers that were highly generalized and employed complex operating systems.

Powerful yet inexpensive small-scale computer systems, which can cost-effectively perform specialized functions, have changed the economics of data processing dramatically. In addition, the unit cost of data storage, which was once the justification for consolidating data in a central location, is no longer the prime consideration. Moreover, the move to DDP can reduce costs in two other areas: (1) data can be entered and edited at the IPU, thus eliminating the centralized tasks of data conversion and data control; and (2) application complexity can be reduced, which in turn reduces development and maintenance costs.

Improved cost control responsibility. Managers assume the responsibility for the financial success of their operations. This requires that they be properly empowered with the authority to make decisions about resources that influence their overall success. Therefore, if information-processing capability is critical to the success of a business operation, then should management not be given control over these resources? This argument counters the argument presented earlier favoring the centralization of organization-wide resources. Proponents of DDP argue that the benefits from improved management attitudes outweigh the additional costs incurred from distributing these resources.

Improved user satisfaction. Perhaps the most often cited benefit of DDP is improved user satisfaction. This derives from three areas of need that too often go unsatisfied in the centralized approach:

(1) as previously stated, users desire to control the resources that influence their profitability; (2) users want systems professionals (analysts, programmers, and computer operators) who are responsive to their specific situation; and (3) users want to become more actively involved in developing and implementing their own systems. Proponents of DDP argue that providing more customized support— feasible only in a distributed environment—has direct benefits for user morale and productivity.

Backup. The final argument in favor of DDP is the ability to back up computing facilities to protect against potential disasters such as fires, floods, sabotage, and earthquakes. One solution is to build excess capacity into each IPU. If a disaster destroys a single site, its transactions can be processed by the other IPUs. This requires close coordination between decision makers to ensure that they do not implement incompatible hardware and software at their sites.

The Need for Careful Analysis

DDP carries a certain leading-edge prestige value that, during an analysis of its pros and cons, may over- whelm important considerations of economic benefit and operational feasibility. Some organizations have made the move to DDP without fully considering whether the distributed organizational structure will better achieve their business objectives. Some DDP initiatives have proven ineffective, and even counter- productive, because decision makers saw in these systems virtues that were more symbolic than real. Before taking such an aggressive step, decision makers should assess the true merits of DDP for their organization. Accountants have an opportunity and an obligation to play an important role in this analysis.

The Evolution of Information System Models

Over the past 50 years, a number of different approaches or models have represented AIS. Each new model evolved because of the shortcomings and limitations of its predecessor. An interesting feature in this evolution is that the newest technique does not immediately replace older models. Thus, at any point in time, various generations of systems exist across different organizations and may even coexist within a single enterprise. The modern auditor needs to be familiar with the operational features of all AIS approaches that he or she is likely to encounter. This book deals extensively with five such models: manual processes, flat-file systems, the database approach, the REA (resources, events, and agents) model, and ERP (enterprise resource planning) systems. Each of these is briefly outlined in the following section.

Comments

Post a Comment