Introduction to Transaction Processing:Accounting Records

Accounting Records

MANUAL SYSTEMS

This section describes the purpose of each type of accounting record used in transaction cycles. We begin with traditional records used in manual systems (documents, journals, and ledgers) and then examine their magnetic counterparts in computer-based systems.

Documents

A document provides evidence of an economic event and may be used to initiate transaction processing. Some documents are a result of transaction processing. In this section, we discuss three types of documents: source documents, product documents, and turnaround documents.

SOURCE DOCUMENTS. Economic events result in some documents being created at the beginning (the source) of the transaction. These are called source documents. Source documents are used to capture and formalize transaction data that the transaction cycle needs for processing. Figure 2-2 shows the creation of a source document.

The economic event (the sale) causes the sales clerk to prepare a multipart sales order, which is formal evidence that a sale occurred. Copies of this source document enter the sales system and are used to convey information to various functions, such as billing, shipping, and AR. The information in the sales order triggers specific activities in each of these departments.

PRODUCT DOCUMENTS. Product documents are the result of transaction processing rather than the triggering mechanism for the process. For example, a payroll check to an employee is a product document of the payroll system. Figure 2-3 extends the example in Figure 2-2 to illustrate that the customer’s bill is a product document of the sales system. We will study many other examples of product documents in later chapters.

TURNAROUND DOCUMENTS. Turnaround documents are product documents of one system that become source documents for another system. This is illustrated in Figure 2-4. The customer receives a perforated two-part bill or statement. The top portion is the actual bill, and the bottom portion is the remittance advice. Customers remove the remittance advice and return it to the company along with their payment (typically a check). A turnaround document contains important information about a customer’s account to help the cash receipts system process the payment. One of the problems designers of cash receipts systems face is matching customer payments to the correct customer accounts. Providing this needed information as a product of the sales system ensures accuracy when the cash receipts system processes it.

Journals

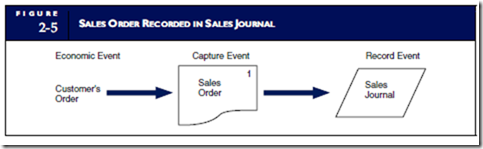

A journal is a record of a chronological entry. At some point in the transaction process, when all relevant facts about the transaction are known, the event is recorded in a journal in chronological order. Documents are the primary source of data for journals. Figure 2-5 shows a sales order being recorded in the sales journal (see the following discussion on special journals). Each transaction requires a separate journal entry, reflecting the accounts affected and the amounts to be debited and credited. There is often a time lag between initiating a transaction and recording it in the accounts. The journal holds a complete record of transactions and thus provides a means for posting to accounts. There are two primary types of journals: special journals and general journals.

SPECIAL JOURNALS. Special journals are used to record specific classes of transactions that occur in high volume. Such transactions can be grouped together in a special journal and processed more efficiently than a general journal permits. Figure 2-6 shows a special journal for recording sales transactions.

As you can see, the sales journal provides a specialized format for recording only sales transactions. At the end of the processing period (month, week, or day), a clerk posts the amounts in the columns to the ledger accounts indicated (see the discussion of ledgers in this chapter). For example, the total sales will be posted to account number 401. Most organizations use several other special journals, including the cash receipts journal, cash disbursements journal, purchases journal, and the payroll journal.

REGISTER. The term register is often used to denote certain types of special journals. For example, the payroll journal is often called the payroll register. We also use the term register, however, to denote a log. For example, a receiving register is a log of all receipts of raw materials or merchandise ordered from vendors. Similarly, a shipping register is a log that records all shipments to customers.

GENERAL JOURNALS. Firms use the general journal to record nonrecurring, infrequent, and dissimilar transactions. For example, we usually record periodic depreciation and closing entries in the general journal. Figure 2-7 shows one page from a general journal. Note that the columns are nonspecific, allow- ing any type of transaction to be recorded. The entries are recorded chronologically.

As a practical matter, most organizations have replaced their general journal with a journal voucher system. A journal voucher is actually a special source document that contains a single journal entry specifying the general ledger accounts that are affected. Journal vouchers are used to record summaries of routine transactions, nonroutine transactions, adjusting entries, and closing entries. The total of journal vouchers processed is equivalent to the general journal. Subsequent chapters discuss the use of this technique in transaction processing.

Ledgers

A ledger is a book of accounts that reflects the financial effects of the firm’s transactions after they are posted from the various journals. Whereas journals show the chronological effect of business activity, ledgers show activity by account type. A ledger indicates the increases, decreases, and current balance of each account. Organizations use this information to prepare financial statements, support daily operations, and prepare internal reports. Figure 2-8 shows the flow of financial information from the source documents to the journal and into the ledgers.

There are two basic types of ledgers: (1) general ledgers, which contain the firm’s account information in the form of highly summarized control accounts, and (2) subsidiary ledgers, which contain the details of the individual accounts that constitute a particular control account.1

GENERAL LEDGERS. The general ledger (GL) summarizes the activity for each of the organization’s accounts. The general ledger department updates these records from journal vouchers prepared from special journals and other sources located throughout the organization. The general ledger presented in Figure 2-9 shows the beginning balances, the changes, and the ending balances as of a particular date for several different accounts.

reporting, but it is not useful for supporting daily business operations. For example, for financial reporting purposes, the firm’s total accounts receivable value must be presented as a single figure in the balance sheet. This value is obtained from the accounts receivable control account in the general ledger. To actually collect the cash this asset represents, however, the firm must have certain detailed information about the customers that this summary figure does not provide. It must know which customers owe money, how much each customer owes, when the customer last made payment, when the next payment is due, and so on. The accounts receivable subsidiary ledger contains these essential details.

SUBSIDIARY LEDGERS. Subsidiary ledgers are kept in various accounting departments of the firm, including inventory, accounts payable, payroll, and accounts receivable. This separation provides better control and support of operations. Figure 2-10 illustrates that the total of account balances in a subsidiary ledger should equal the balance in the corresponding general ledger control account. Thus, in addition to providing financial statement information, the general ledger is a mechanism for verifying the overall accuracy of accounting data that separate accounting departments have processed. Any event incorrectly recorded in a journal or subsidiary ledger will cause an out-of-balance condition that should be detected during the general ledger update. By periodically reconciling summary balances from subsidiary accounts, journals, and control accounts, the completeness and accuracy of transaction processing can be formally assessed.

Comments

Post a Comment